Battle for Elst (September 1944)

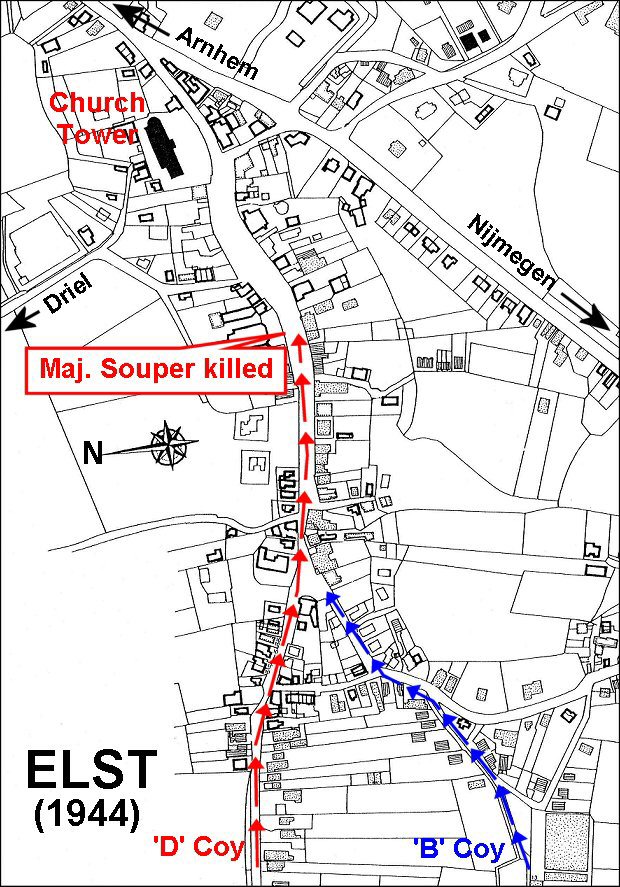

The Worcestershire Commanding Officer was visited by the Brigadier and was told that 1st Worcesters, in conjunction with the 7th Somersets, were to take the town of Elst. It was then 12.00 hours (23rd September 1944). Accordingly plans were made but evidently things were not going fast enough, for at 15.00 hours the Divisional Commander came and stated that the attack must take place as soon as possible—16.00 hours, ‘H’ hour.

Standing by the Gunner Command Vehicle an hour later one could hear the word ‘FIRE’, a rumble in the distance, the shriek of a shell passing over, and then crash—our artillery were preparing the advance. ‘D’ Company leading, with tank support, set off down the road, passed through ‘C’ Company’s location then swung to the left, then to the right. A crash of 88’s greeted their appearance as they debouched into the open country, and small arms fire spattered from various farm buildings. The tanks replied, the Company deployed, and the advance continued. At a bend in the road a Panther appeared, but its life was very short for it was instantly set on fire by our own tanks, a credit to their alertness. The farmhouses were searched and the enemy found in them were quickly disposed of.

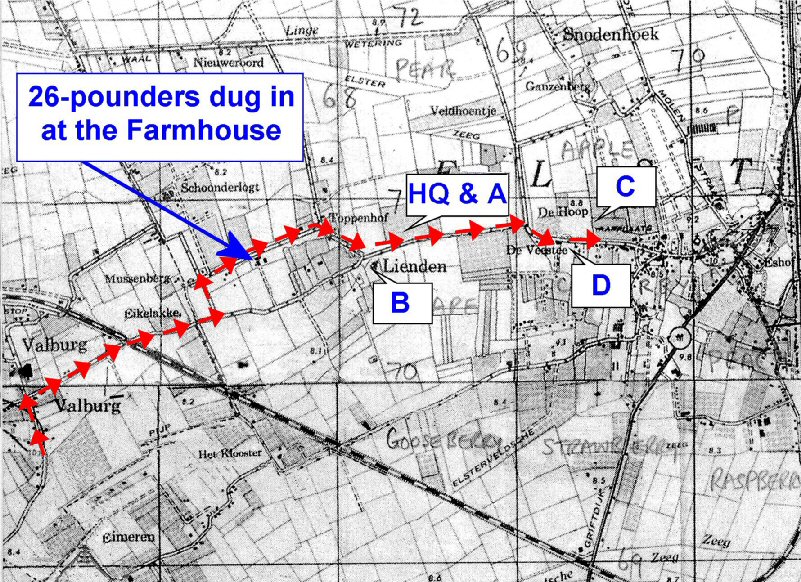

Advance of “D” Company – German tanks numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4

The German tanks indicated in the map above; 1 was destroyed, 2 and 3 were in the ditch at the side of the road track (having previously been put out of action by the 5th DCLI), 4 was shooting at the farmhouse and was destroyed by our supporting artillery.

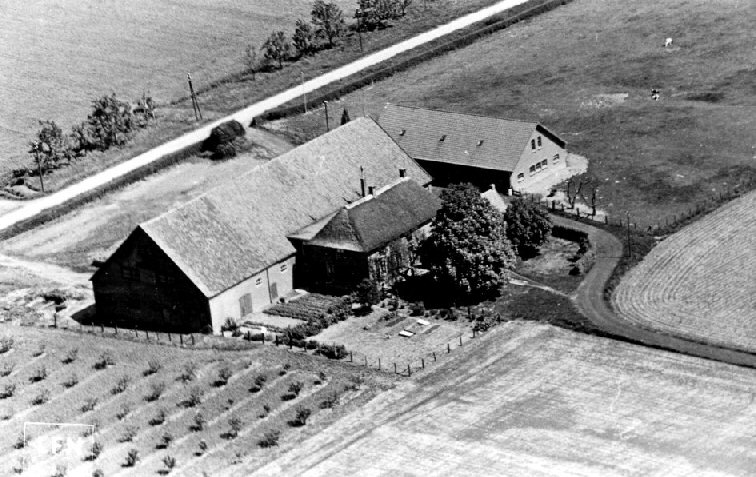

The Farmhouse on Mussenstraat (the De Regt family)

Aerial view showing (top centre left) the De Regt family |

‘D’ Company proceeded on the road track running passed the farmhouse (seen on the photo above). After another two bends it was a long straight road towards the entrance to Elst, and a tall church steeple in the town itself gave one the feeling (and it was later proved to be correct) that this, as an observation post, gave the Germans a perfect view of our oncoming attack. ‘C’ and ‘A’ Companies emerged from their slit trenches and followed. Solid shots twanged over their heads—another Panther appeared and was engaging our own thrusting force of tanks—darkness descended quickly and the Worcesters struggled forward against the strong resistance; at last, the second Panther which had been holding them up was destroyed.

Lieut. Johnnie Davies (‘A’ Company, 7 Platoon) recalls; |

Lieut. Johnnie Davies |

And so, I spent Christmas comfortably in Southend convalescing. I rejoined the regiment in time to participate in the battle of the autobahn, which of course is another story.” Finally, the outskirts of Elst were reached. ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies took up positions just inside the town on the left and right of the road, ‘A’ Company lay back in an orchard with Battalion H.Q., and the Machine Gunners covered the open ground to their left. ‘B’ Company was in rear, with the Mortar Platoon in position close by them. It was impossible to undertake house-clearing at night so the Commanding Officer ordered consolidation in those positions, and by torchlight made plans for the final assault the following morning, the 24th September. The night was comparatively quiet, except for the occasional burst of fire, the tracers from which described fantastic patterns in the sky, and the periodic rumble of tank tracks. In the distance the sky was lit up by flares, enemy bombers were attempting to destroy our life-line at Nijmegen, and it was here yet again they had news that the one route through Holland had been cut by a determined enemy counter-attack—not a pleasant position for us to be in.

|

Company positions night of the 23rd September 1944

Dawn broke (24th September) and all was quiet, the attack on Elst must be finished today. No great artillery support could be given as shells were now rationed owing to the supply-route being cut.

The plan was as follows: ‘A’ Company were to swing out into the open country, north of Elst, to protect the flanks of ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies who were to do the actual clearing, ‘B’ Company first and “D” Company second. ‘C’ Company were to remain in their present position.

It was just about to be executed when the sound of an enemy tank was heard just round the corner before one entered the town proper. Our Tank Commander decided to see if his own tank could knock it out, and, acting as gunner, he ordered his driver to nose very cautiously round the corner. The tank eased forward, slowly, very slowly, then crash—a sheet of flame, and it immediately reversed again. Someone peered round the corner and there was the Panther—killed—his turret had been facing the wrong way. On investigation later it was found that this tank, together with others, had come straight from the factory to this front.

Company movements and positions on the 24th September 1944 |

Major Knaust |

At this time Elst was occupied by the 10th SS Panzer Division 'Frundsberg' commanded by Major Knaust, with tank support. They were well dug-in with troops occupying most of the houses. On the 24th September they were reinforced with Two Königstiger companies from the 506th Schwere Panzer Abteilung.

Private Albert Kings (‘B’ Company, 12 Platoon) recalls; ‘A’ Company reached their flank position without much trouble and our Mortar Platoon started dropping their bombs in the town. ‘D’ Company eased forward and the leading section was greeted by intense automatic fire. It seemed that in every house there was a German with an automatic weapon. Major Souper (the Company Commander) dashed forward to rally his men and lead the Section. They ran from cover to cover, dashing and throwing grenades in open windows and trying to destroy the stubborn and heavy resistance, but it was too good to last, whilst running across an open space a burst of fire struck Major Souper, mortally wounding him. It was a fateful town. |

|

Private Albert Kings |

Pte. Arthur (Ken) Neale recalls killing of Major Souper; “During the fighting at Elst on the 24th September 1944 `D' company eased forward. The leading platoon (16 Platoon) of about fourteen men commanded by Lieutenant Ron Jauncey were held up by machine gun fire coming directly down the main street towards our position which was located at the other end of the street in a patch of open ground. |

Major Mowbray Morris Souper Major Souper's batman Private Harding came back and reported to Captain Elder the sad news that Major Souper had been shot and killed. A while later Private Harding went back with the stretcher-bearers and moved Major Soupers body in to a building so they would be able to find him later after the battle, when they would come and collect his body with the Padre. |

Private William Rees (14711451) Private Rees, killed by German machine gun fire as he crossed the main street in Elst with Major Souper. |

Lieut. Ronald Henry Jauncey |

The battle raged on and nearly every building was set a fire and the whole town was ablaze. When Private Harding and Padre Captain William Speirs came back to collect his body, they found it had been badly charred by fire. They evacuated the remains and he was duly burried with other dead in a temporary graves in a small orchard next to the Klassen family farmouse at Lienden on the Valburggesweg, near Elst. At the time this was also the location of Battalion H.Q. At the time an 11 girl living at the farm recorded all the names of the dead in her note book and at the bottom of the list of names (14 Worcestershire and 12 Somerset men) she added the words "Dit zijn de namen der gesneuvelde Thommie's" (These are the names of the killed Thommie's). After the war all the graves were moved to the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetry. |

|

L/Cpl. A. H. Palmer

|

During this fighting Lance Corporal Alfred Henry Palmer (5257827), from Redditch, who was commanding the forward section of 16 Platoon of ‘D’ Company located the enemy machine gun post. He approached it from the right flank, and on taking the first obstacle, a hedge, his automatic weapon was struck by a bullet from another enemy post only five yards away. Corporal PALMER held on to his weapon, and single handed without regard for his own personal safety, completely wiped out the post leaving five enemy dead, so enabling his section to continue their attack on the located enemy post. For his action that day he was later awarded the Military Medal. |

|

Captain Bryan Elder |

Ditched Tiger Tank at de Hoop crossroads |

|

Captain Bryan Elder recalls; “The enemy occupied the houses and automatic fire was unceasing. My Company Commander Major Mowbray Souper rushed one of the enemy posts, which covered the roadway into the |

||

town, and was killed. He had commanded ‘D’ Company since early Normandy, and was a man of great charm, ability, and personal courage and it was a privilege and honour to be his second in command. At the very time he was killed, I am attending to a Sergeant (Lance-Sgt. Horace Arthur Ward) who had been wounded and lay dying in my arms. I was devastated, shocked, and unbalanced to say the least, but it was no good showing this to anyone.

So I took over the Company awaiting further news. We had not received any rations, but to my relief a Dutch Farmer brought a load of ham sandwiches and after requesting him to eat one to check that they had not been poisoned (don’t forget Germans were still in occupation of some of the houses), one more problem was overcome. The Tower of Elst Church was shelled by our anti-tank section to clear out any German observers which resulted in the local inhabitants taking refuge in the Church coming down the road to a School building opposite the cemetery where we had dug our trenches the night before. The Adjutant came up on his motorcycle and confirmed that I was to take over the Company as Company Commander.”

At this particular moment a shower of mortar bombs rained down on the Companies. The Commanding Officer decided that the church tower was an observation post and ordered the Anti-Tank Platoon to destroy it. Shot after shot thudded into the solid brickwork but it still stood firm, our only consolation was that if there was an observation post in the building, its occupants were having a very uncomfortable time.

‘D’ Company temporarily halted, ‘B’ Company were pushed through, and after some very tough and hand-to-hand fighting, reached the end of the town. The Commanding Officer then ordered everyone to consolidate in their present positions, ‘A’ Company to send a Platoon forward to establish itself on a small mound in front of their locality.

A line party from the Signal Platoon earlier laid a line forward to the mound, thinking that the Platoon was already in position out there and, on being unable to locate them, reported back to ‘A’ Company H.Q. stating that the line had been laid and that everything was in order. On receipt of this news the Platoon was immediately sent out again to take up the position.

Coporal Bill Gould (Signals) , recalls; “I was detailed to lay a line to a small mound north of the village in the direction of Arnhem, where I was told ‘A’ Company had put in an attack to take possession of it. They urgently required communication, and viewing it from my position it looked like a desperate outpost in ‘No mans land’. It was with much trepidation that I moved towards it with my little party, who made it known to me that their heart was not in the job. The information we had been given was dubious and it was plain to see that there was no life in the area and it was still in possession of the enemy. We moved forward slowly and as we were not fired on we took courage and duly arrived, finding the spot empty. We dug a suitable hole, planted a field telephone in position and beat a hasty retreat to the rear. On reaching the outskirts of the village, Major Gibbins, the Major commanding ‘A’ Company, emerged from a doorway and accosted me with: ‘Where the Bloody hell have you been?’. I replied with some pride: ‘We have laid on communication to your unoccupied post’. ‘The hell you have’ he replied in some exasperation, and took his men forward to the objective. Some time before he had tried to get his men forward but they had met with terrific machine gun fire and had retreated again to the shelter of the houses.” Later that day, whilst proceeding to the mound, a Platoon of ‘A’ Company met an S.P. gun and, after suffering several casualties, were forced to pull back to their original position. |

Coporal Bill Gould |

During the night the forward platoon of ‘A’ Company, led by Lieut. B. Bagley, while digging in suddenly came under enemy attack. Some 16 German infantry opposed them with small arms and machine-gun fire. They were beaten off with Bren and rifle fire and retreated into the nearby woods. But within twenty minutes sounds of a tank was heard creeping up the road towards them. “It came to within 15-20 yards of us,” said Sergt. F. Jones, platoon sergeant. "It then opened up with its 88 millimetre gun on our forward section, and fired six rounds at them. The crew of the PIAT fired several shots at the tank, but the forward section had to withdraw. We then heard other tanks moving round our right flank to cut us off. Contact was broken with company headquarters at the time. We wanted PIAT ammunition." Two men were sent back and eventually made contact with ‘A’ Company headquarters and they quickly returned in a Jeep with Sergt.-Major L. Thomas, and twelve PIAT bombs.

All this time the platoon was being closely engaged and threatened from the flanks and gradually lost ground. Its retirement was covered by a courageous Bren gunner (Private Norman Stokes) who from a standing position engaged the tank with small arms fire. The platoon got astride a dyke. "We were fortunate in that the bank gave us protection from the tank's 88 millimetre gun," said Lieut.Bagley. "Its fire brought down the overhead cables and the leading section was pounded badly as we pulled out,"

On the arrival of the fresh PIAT bombs, Private Norman Stokes and Private Reginald Lugg went into action against the tank with the PIAT projector. With covering fire and support, from Sergeant Jones and Private Downes, they took up position by the railway crossing.

The Tiger was destroyed as a result of the close range fire from the PIAT. The platoon eventually succeeded in withdrawing from a hazardous position after a brave night battle against armour.

For their courageous action Private Norman Stokes and Private Reginald Lugg were both later awarded the Military Medal.

As nightfall came all was quiet apart from some local patrol activity.

The next morning (25th September) Major Gibbins (commanding ‘A’ Company) took his ‘O’ Group round his Company locality to re-arrange their positions. Whilst standing with them by a house, it was struck by a shell from an ‘88 mm’. He was killed and the men around him were wounded.

The rest of that day (25th September) the Worcesters spent time clearing up and licking their wounds. Visits were paid to the Dutch people who had remained in the town, encouraging them and asking them to leave, but quite a number preferred to stay now that the town was in our hands. Later history relates how they were all evacuated as the town was pounded into rubble and months later flooded by the breaching of the dykes. In the afternoon a terrific explosion and a long column of smoke arose on Worcesters’ left flank. The blast was enormous and it later transpired that a 6-Pounder Section of the 5th DCLI had seen some German troops working on railway trucks, apparently unloading them. The DCLI had fired at them, and that was the result. The Worcesters were shelled spasmodically but no damage was done. A party of men had the grim task of digging graves in the orchard by Battalion H.Q. for their unfortunate comrades who had fallen in Elst.

Lieutenant Rex Fellows |

Lieutenant Rex Fellows (‘B’ Company, 12 Platoon) recalls; A shell had conveniently blown a hole, perhaps two feet square, in the back wall. An old mattress lay on the floor to comfort the firer’s position. The extraordinary thing was that the outline of the hole in the brickwork framed the four bodies, in the manner of a camera framing! The area had four bodies in it as if they had been posed! It was concluded that after the initial shot the others had gone to ground and stayed where they were. It was a fatal mistake. They would, of course, have had the greatest difficulty in locating the enemy, but had they gone only slightly to the right, perhaps by rolling away as they had (hopefully) been trained to do, the trees would have screened them from view, they might have survived.” Private Douglas Burdon (179 Field Regiment R.A.) supporting the 1st Worcesters recalls; “Captain Roy Woodward (F.O.O.), Nobby and I were with a detachment of Worcesters in an orchard on the outskirts of Elst when a 15 cwt truck of the Worcesters came bowling through the gateway and bumped across the grass to where a group of men stood waiting. As it passed us we saw the studded boots of the dead men in it. The rest of their bodies were covered with army blankets. |

’Here you are, sarge. Another bunch of stiffs for you,’ the driver called out as he pulled up close to the group. The 'stiffs' were some of his own mates who had been alive only half an hour before. The orchard proved to be of no use to us as an observation post so we clambered into Roger Dog and drove out of the orchard, turned left at the gate, and headed towards Elst. There was a right-hand bend not far along the road and as we swung round it we were confronted by something that made us gasp with alarm. Right in front of us in the middle of the road was a Panther tank. Nobby trod on the brakes so suddenly that the rear end of the carrier rose up sharply as if trying to overtake the front end, and for a fraction it seemed to be suspended there, then it fell back with a bump and rocked to and fro once or twice before becoming still. For one awful moment we thought our time had come and we would be blasted out of existence by the tank's 88mm gun, until we saw, to our heartfelt relief, that it was pointing the other way. We had come up behind it. In an instant, and without stopping to think, Nobby and I leapt out of our seats, sprinted across the intervening few yards, and leapt on to the back of the tank. Nobby thrust the muzzle of his Sten gun into the turret the moment I yanked the hatch open. Then his look of grim determination turned to one of complete amazement. ‘It's empty. There's nobody in it,’ he said, and dropped down inside while I kept watch in case the crew should be in the vicinity. When he emerged he was still surprised. ‘It's a new one. It's only got forty-five kilometers on the clock. It must have been driven from the nearest railhead and then abandoned.’ Not to have captured it 'live' was something of a disappointment, but we could always tell our mates that we had captured a Panther tank single-handed! |

Private Douglas Burdon |

The house and orchard on the outskirts of Elst where the Worcestershire dead where taken and buried in temporary graves

The high level of activity in the area compelled us to remain there, because we did not know what the outcome might be nor who might require artillery support. Using the tank for cover we kept a close watch on the road and the village. To our immediate left stood a large, detached, square-built house with rhododendrons in the front garden and iron railings round the garden. A sudden explosion set the rhododendrons swaying and rustling as if a strong breeze had disturbed them. The unexpectedness of the explosion startled us, and just for a moment we hesitated, uncertain of our next move, then, leaving the cover of the tank, we went to investigate. A convenient gap where the railings were bent enabled us to squeeze through and we walked quickly but carefully through the bushes. In the open space in front of the house was one of our anti-tank guns with its crew crouched behind it. We heaved sighs of relief. ‘Blimey, sarge, you might have warned us,’ said Nobby. ‘We thought we were being got at.’

The Panther Tank with its gun facing to the rear |

The sergeant grinned good-humouredly and went on giving his orders to his crew, and we were relieved at not being a target for enemy guns returned to our position behind the tank and resumed our watch on the village. The Germans had been using the church tower as an observation post but someone had put a shell hole halfway up it and forced them to evacuate it. They could still be in the vicinity for all we knew. A small group of people appeared unexpectedly from the direction of Elst and hurried towards us, and as they drew nearer we saw there were about ten of them, ranging in age from young children to pensioners. They were no more than twenty yards from us when a deafening salvo of gunfire came from so close at hand we could only stare in |

amazement and disbelief in the direction from which it had come. We did not know where the guns were, nor whose they were. The refugees flung themselves, crying and whimpering, into a ditch at the side of the road and lay there, terrified. Then we saw them. One Battery of guns, half hidden among the trees beyond the field to our right. The gunners wore battledress, and the guns were our own 25-pounders. Somehow, they had managed to push right forward and catch up with the infantry. How they came to be there we neither knew nor cared. Their presence was as welcome as it was unexpected. I stepped from behind the tank and strode quickly along the road to where the refugees lay huddled in the ditch and beckoned to them to come to me. "It's O.K. Englisher cannon," I shouted, pointing to where the guns were hidden. "Englisher cannon," I repeated. One by one they rose slowly to their feet, looking uncertainly in the direction of the guns. Another salvo battered our eardrums, and they flinched and started crying afresh and seemed about to dive into the ditch again. I stood where I was, beckoning them on. It seemed to reassure them and they came hesitantly towards me. I shepherded them behind the tank. They were all crying still, but whether from fear or relief we knew not. The older men and women squeezed our hands and held on to us as if their safety depended on their not letting go; the children clung to our legs as though they idolised us; and the young women flung their arms around our necks and kissed us as though we were long-lost dear ones. When they were all more or less composed and had dried their eyes one of the younger women spoke. “Valburg?” she asked. “Valburg?” I nodded. "English in Valburg," I told her. There was more squeezing and kissing, then they set off towards Valburg. I hope they made it.”

|

Elst Church tower after shelling |

View of the Railway Station at Elst

Major Bryan Elder later wrote to Major Mowbray Soupers motherAfter Major Souper was killed at Elst, Bryan Elder who up until then was second-in-command took over command of ‘D’ Company. After Bryan Elder was himself wounded on the 14th April 1945 during the battalion’s last battle of the war and was back in the U. K. recovering in hospital he was contacted by Major Souper’s mother. She asked him to write to her about his time with her son. At the time Bryan Elder was at Park Prewett Army Hospital at Basingstoke. Below is a copy of what Bryan Elder wrote to Major Souper’s mother:

I knew that he was proud of his Company and it was not long before I knew that everyone in the Company more than respected their Company Commander. There was no doubt that he led ‘D’ Company. I learnt of the history of the 1st Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment and ‘D’ Company. As I moved around the Battalion I found everyone knew Major Souper. I could enlarge upon this point but it was so marked that I knew I was in capable hands. The strain of the previous hard battles was telling upon him, and he was slightly off colour to develop a chronic stomach pain. Harding (Major Souper’s batman), whom I already regarded as a very faithful and able servant went back with Mowbray to the R.A.M.C. Temporary Hospital. He had two or three very troublesome days, and a Regular Major from the Worcestershires who was later killed near Elst while commanding another Company (Major "Horsey" Gibbins) came to take over the Company. Mowbray was not quite fit when the Battalion moved towards the Seine. He caught the Battalion up and joined Battalion H.Q. and the C.O. (Lt-Col. Osborne-Smith) decided to rest Mowbray from the crossing of the Seine. Let it suffice to say that the Battalion crossed the Seine and ‘D’ Company had a successful day. I heard that Mowbray had now joined the Battalion Adjutant (Captain W. L. Leadbeater) at Battalion H.Q. Next morning, August 26th, the battle was fierce, and the enemy counter-attacked with Tanks and Infantry. At one time it looked as though the enemy might break through, but they did not. We lost many gallant ones that day. We stabilised the position before dusk and both sides dug in with some 200/300 yards No Man's Land. It was known that there were many wounded on the Hill-side. Mowbray had throughout the whole battle devoted himself to evacuating the numerous casualties. Now he organised a party to search for the wounded. Yes, many men must have owed their lives to Mowbray. It seemed natural to the Battalion that "Soup" should be doing this work. He had done it before on many occasions when other Companies were committed and having heavy casualties. Capt. Duff-Chalmers (R.A.M.C.) the Medical Officer, will more than testify to his unrivalled reputation for getting in the wounded. Capt. Duff-Chalmers was wounded (fractured leg) on April 10th. (I could find his address for you if you wish). On the night 26th/27th I was out on patrol with two men. The enemy was waiting for us and we were welcomed by small arms fire. Both the men were hit and only just managed to get back. I was having trouble in getting the two men back when who should turn up in the darkness but Mowbray. He helped carry one chap back whose left arm was badly smashed (Private George Pound, Major Elder’s batman). He helped with the second chap (Private Cyril Stotesbury). Never was I more glad to see someone, and it could not have been anyone better than Mowbray. He knew how I felt, and I know that I thanked God time and again for sending "Soup" to my side. Both the men survived and I have had letters from them both. Next day, 27th August, we moved to a village near Vernon called Pressagny where we stayed for approximately 14 days while the rest of the Army chased through Belgium. During this fortnight Mowbray and I found out that we had much in common. We were billeted in the out-buildings of the village cottages. The weather was perfect and we spent many hours on the Seine either boating or rafting or even bathing. Mowbray and I tried to get to Paris on the same day, but he had to go off with Major Broom and Lieut. Rex Fellows. I remember everyone having some birthday cake. Bunty (Major Soupers wife) had sent their only daughter's birthday cake. During this time Mowbray talked much of life at home, speculating as to the future. When we moved forward again I knew Mowbray as my friend - we went everywhere together, and thoroughly enjoyed ourselves changing into rough clothing and going for a long ramble. Never once during the whole fortnight did he put his consideration before the men’s. Now we were to run through the Continent, skirting Brussels and on towards Grave. I do not remember the dates very well but it must have been something like the 19th September 1944 when we harboured up against Nijmegen. We saw the Airborne Division going overhead, and we knew that shortly we were to be with them if all went well. We were terrifically optimistic at the time. On the 22nd September we went forward and waited on the road near Nijmegen. The plans were changed and we heard we were in for a different battle. We were pushed forward to Valburg by night and on the morning of the 23rd we tried to get forward to the Airborne. The 1st Worcs were ordered to the right flank to take Elst before dark. Two Companies went forward – ‘D’ Company on the left. We got forward to the first Cottages due east of Elst - opposition was not too terrific, but as we were ahead of the others we were ordered to dig in for the night. Our area was more or less a bog, but we managed to dig our fox-holes. There was practically no rest that night - there was no interference by the enemy but we were ordered to prepare to advance at first light. After an Artillery Barrage we went forward and after surprising the out-post sections the Company reached the base of Elst. We were ordered to capture the (triangular) group of houses due east of Elst. The left forward platoon had been halted on the left and Mowbray went forward with Harding to see what was holding them up. He always moved about the battle field with complete confidence and did not register any fear. Courage and devotion to duty completely predominated. The next thing I saw was Harding coming towards me and there was no need for him to say anything - I knew the worst. I asked Harding if there was anything which could be done, and he said "No". I left him in a ditch and I believe he just wept for a while. I realised my responsibilities and took the stretcher-bearers forward to the left. The battle was very fluid. To get control I stopped everything on the left, at the same time the Platoon on the right got into difficulties. I was compelled to rush over to stop anything happening there. I was there about an hour in anything but a secure position. When I got back to the left the stretcher-bearers had confirmed the worst. I was told by the Platoon Commander that Mowbray came forward. He realised that the opposition came from some houses on the right. Just like Mowbray, he got two men and decided to rush round the left. They started off, but a burst of machine gun fire came amongst them and all fell. Mowbray was killed instantly, and only one of the other two was able to be evacuated. The stretcher-bearers and Harding moved Mowbray into a building to make certain that they would be able to find him when they came to collect him with the Padre. They did this at considerable risk to themselves. After that the battle raged very furiously. Nearly every building was set on fire and the whole town was ablaze. Next morning after the fires were abating, and the enemy were beginning to withdraw, we searched the buildings to find Mowbray's body very badly charred. The Padre and Harding evacuated the remains and he was duly buried in the Battalion Cemetery. Mowbray's spirit lived on in ‘D’ Company. Yes, I seized upon it for my own guidance and his example was a steadfast help in troubled times. He showed me how to lead men, and I tried my best to step into his position. We fought on to avenge ourselves, and I was always mindful that the enemy had taken the best leader I should ever have, and my friend. I was blessed by God to lead ‘D’ Company to the very last battle. They never let Mowbray down, and all the men who knew "Soup" were always the best in difficult times. Harding was wounded on the 18th November 1944 when advancing near Geilenkirchen (Tripsrath). He was hit in the arm and is now discharged from the Army. You will realise now why we could not send back Mowbray's personal kit, wallet, watch, etc. This has not been easy to write and I apologise for the short-comings. I hope you can read it as I have written it lying on my back. I hope to be up next week. I have just re-read the above and it reads like an autobiography. One thing is certain, and that is the fact that I have not over-acted Mowbray's devotion to duty - I could not if I tried to."

Dutch school girl Riet Wetsteijn tends the grave of Major Souper Oosterbeek War Cemetery 24th July 1946 |

|

Story of Lance-Corporal WilkinsLance Corporal William Leonard Wilkins originally of the Staffordshire Regiment joined the 1st Battalion Worcestershire Regiment early in September at the Seine with a large draft of reinforcements from the 59th Division, which had been disbanded. Later in a letter he wrote to his wife Ivy, dated 22nd September 1944, he tells of a relatively restful night in the gardens of Dutch homes beneath the bridge at Nijmegen. They had taken the bridge and were about to make their way up that infamous ‘corridor’ to Arnhem. He wrote with confidence of his “trusty Bren gun”. He wrote of the exhuberant welcome of the Dutch people and he wrote of his unwavering love for his wife and 2 year old daughter Linda. He did not write of the incessant rains, nor of the failure of communications, nor of the German tanks hidden beyond the trees, nor of the upcoming arduous journey on those narrow, muddy dyke roads. On 25th September 1944, his wife received a letter from the war office. Lance Corporal William Leonard Wilkins had been killed in action and buried in an apple orchard near Elst. But she did not know the exact place then, nor did she even want to believe he wasn’t coming home. Yes, the gift of peace and liberty came with a hefty price tag but it was not lost on those gallant women who carried on without their men, women like Ivy Winifred Wilkins who in 1947 sold her most prized possession, her mother’s piano, and with 40 pounds in her pocket took her baby daughter Linda to a new life in Canada, taking a job as a chambermaid in Toronto to make ends meet and eventually marrying a Canadian veteran. But England, and Holland, were never far from her thoughts. She visited her beloved homeland and Holland just twice over the next 47 years. Both trips were intense pilgrimages rather than holidays. And, she continued to research, writing hundred of letters, stories and poetry until she died in April, 2001. On 14th May 2002, Linda Wilkins-Parker (Lance Corporal William Leonard Wilkins daughter) and her son took Ivy's ashes to the Oosterbeek War Cemetery in Holland. Dozens of the dear Dutch friends she had met though her research gathered as they placed her Mum’s remains in the war grave of her father. Fittingly, it would have been their 63rd wedding anniversary. |

Lance-Corporal W. L. Wilkins |

Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery (1947)

|

Lieutenant-Colonel P. H. Graves-Morris (later Brigadier) visited the War Graves Cemetery outside Arnhem in 1947, saying; “It is very pleasantly situated, surrounded by poplar trees and is well looked after; many graves are tended by villagers in the neighbourhood. The crosses are made of iron and painted white; the inscription on each is done in black lettering.” The photograph above (taken in 1947) shows a section of the cemetery, which many 1st Battalion Worcestershires who gave their lives during the battle for Elst were laid to rest. |

Oosterbeek War Cemetery lies 7 kilometres west of Arnhem on the road to Wageningen. From the Utrechtseweg, turn on to the Stationsweg heading for Oosterbeek Station. At the railway station, turn right on to Van Limburg Stirumweg. The entrance to the cemetery is a short distance along this road opposite the town cemetery.

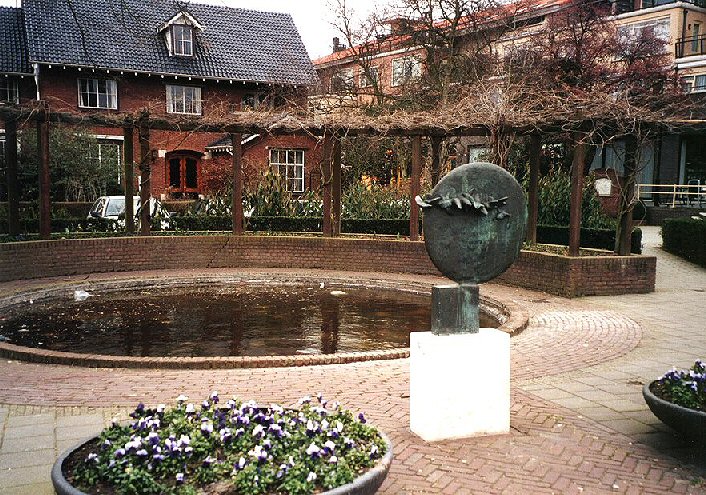

Memorial in Elst

The Liberation Monument at the Town Hall, Dorpstraat, Elst

The monument consists of a travertine plinth with the following inscription: “ Elst op 25-09-1944 bevrijd door 7 Somersets L.I. Regt., 1 Worcester Regt, 4/7 Royal Dragoon Guards” Translated “Elst on 25-09-1944 liberated by 7 Somersets L.I. Regt., 1 Worcester Regt, 4/7 Royal Dragoon Guards”. Above which is a bronze square block with a shield and the image of a flight of birds flying past. The balancing of the shield on the edge of the block symbolizes the continuous terror and threat. The shield symbolizes resistance and the flight of bird’s freedom. The monument made by Marina van der Kooi of Amsterdam was placed here on the 17th September 1984 (40th anniversary of the battle at Elst).

|

Liberation Monument inscription |

The damaged main street in Elst after the battle

|