" THE GLORIOUS FIRST OF JUNE 1794."

The French Revolution which broke out in 1789 was at first re-garded with some sympathy in England, but the excesses of the Revolutionaries as the movement progressed, culminating in the frightful massacres of September, 1792, alienated British opinion. Then the Revolutionary government despatched agents to stir up trouble in England and the other neighbouring countries. Attempts from abroad to influence our home politics have seldom been warmly welcomed in England, and the activities of the French agents roused the country to alarm and anger. Not content with subversive pro¬paganda, the Revolutionary government launched armies to over-run Belgium (then a dependency of Austria) and Holland. The Dutch appealed to England for help. The British Government informed the French representative that England could neither allow Belgium to be incorporated with France, nor tolerate an invasion of Holland. The Revolutionary Convention replied, on February 1st, 1793, by a declaration of war.

At that date ten years of peace had elapsed since the conclusion of the unfortunate War of American Independence. In that interval the British Army and Navy had been cut down to the barest minimum. The Army was so reduced that of the Line regiments only twenty-eight battalions, all much under strength and mostly filled with young boys, were available at home; and most of those were needed to keep order in Ireland.(1) The Navy was in little better case. Hasty impressment of seafaring men enabled the majority of the British warships to be put into commission, but in those days marines formed an essential part of a warship's complement, and trained marines did not exist in sufficient numbers. So the best-trained soldiers of several Line regiments were hastily requisitioned for duty on board the Fleet. The 29th Regiment, which in January, 1793, had left Windsor for billets around Petersfield, was among those selected to find drafts for the Fleet. The Regiment moved to Hilsea Barracks and thence successive detachments were embarked in various ships during the early months of the year. The troops were specially equipped for this service, being issued with a "working rig" of blue flannel jackets with turn-down collars of the regimental facings (then pale yellow), trousers and check shirts; but they took on board with them their proper regimental uniform—red coats, white breeches, and black gaiters—to wear in case of action. |

|

During the next two years those detachments of the 29th served on board the warships—a far harder and rougher service than life at sea to-day. The ships were small, by present standards, and crowded with men. Accommodation for the most part was limited to hammocks slung in the low badly-lighted gun decks, and the food was anything but good—cold salt "junk" and hard biscuits were the staple provender, and both were too often in bad condition. The squadrons were constantly at sea, beating up and down the stormy Channel and watching off the French ports for signs of attempted invasion.

In those days the duties of marines on board a warship were manifold. In action they manned the open upper-deck, to meet by musketry fire any attempt to board or themselves to lead boarding parties. Between whiles they were expected to assist in the general work of the ship and especially in the maintenance of discipline, for the ships' crews were a rough lot of seamen, many of them forcibly impressed; and naval discipline, although informal in many ways, (2) was very severe.

Despite its roughness, the service had its compensations. One of the first detachments of the 29th embarked in H.M.S, "Edgar" on the 13th February, 1793. In April the "Edgar" sailed from Spithead with a small squadron to patrol the Channel, and on the 15th April "Edgar" and "Phaeton" ran down a French privateer which was escorting a captured Spanish treasure-ship from South America. After a short engagement the enemy surrendered, and "Edgar" towed the treasure-ship back to Portsmouth, where the booty was found to be prodigious—some £1,300,000. The "prize-money" awarded brought £60 to each soldier of the 29th on board the lucky "Edgar," £300 to each sergeant, and proportionately larger amounts to the detachment's officers.

Such incentives kept the crews of the Fleet in good heart during the long first year of the war. On land the campaign in the Low Countries proceeded intermittently, and British troops under the Duke of York fought around Menin, Cambrai, and Valenciennes; but at sea there was no great fighting. The Revolution had resulted in the dismissal or murder of nearly all the former aristocratic officers of the French Navy, the old discipline had been destroyed, and it was not easy to form a fleet fit to meet the British at sea. Con-sequently for over a year after the declaration of war the French squadrons remained inactive in their ports. Not until the spring of 1794 did they risk a general engagement. By that time the new crews of the French ships were fairly well trained; and what they lacked in training they made up, in the eyes of their leaders, by enthusiasm for the World Revolution.

In the last week of May the French fleet put out from Brest. The immediate object of the cruise was to meet and escort into harbour a great convoy of food ships from America to France. To intercept that convoy the British Channel Fleet, commanded by Admiral Lord Howe, had sailed from Spithead on May 2nd. In the Channel the weather was stormy towards the end of May, and a heavy sea was running when the two fleets sighted each other off Ushant on the 28th of May.

In those days of sailing ships Naval tactics were complicated by dependence on the wind. Given the weather-gage, a skilful admiral could either force or deny an engagement. The object of the French admiral, Villaret-Joyeuse, was to delay matters until the convoy from America was safely in port, and for the next two days he successfully avoided battle, drawing the British fleet after him. (3)

There were sharp bursts of firing from such few ships as could get within range, but the main British battle-fleet was unable to close. Throughout that time a fierce gale blew from the south-west, and the heavy, crowded ships pitched and rolled in an angry sea.

On May 30th the gale abated, and a dense fog shut down over the two fleets. So close were they that the ships' bells of the enemy could clearly be heard, but only occasional glimpses appeared of the enemy's topmasts, or of the heavy hulls rolling in the long swell of the sea. The fog lasted until mid-day on May 31st, when it cleared, and it could be seen that the British fleet had gained on the enemy. That evening and all that night Lord Howe's fleet pressed on, and by dawn of June 1st they had gained the desired position—they had got the weather-gage of the enemy and could force them to fight.

Having gained the desired position of advantage, Lord Howe prepared for battle. First he made a signal for all hands to breakfast, then, after some time spent in altering the order of his ships, he made the signal to engage; and in fine weather and bright sunshine the British fleet bore down on the enemy.

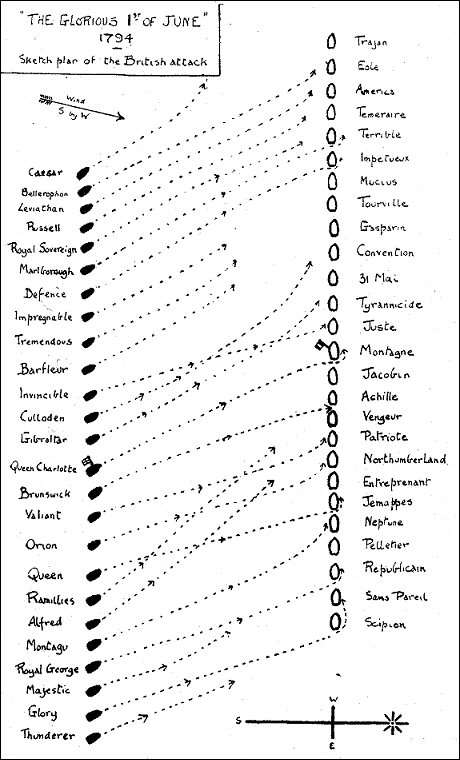

Numerically the two fleets were not ill-matched, though the advantage lay with the French; who could match twenty-six battleships against twenty-five(4) of the British. Their guns were rather heavier than ours, and their crews totalled some 20,000 men against 17,000 British. But Lord Howe was confident of the superiority of his men in efficiency and discipline, and his plans were boldly made. The French fleet to starboard was moving in line ahead. The British fleet was to approach obliquely in line abreast. Each British ship was to pass through the gap between two French ships, raking them fore and aft as she passed, and was then to close with the foremost of her antagonists on her lee side, thus making her escape impossible and forcing her to fight to a finish.

In the event the plan was not completely carried out. Confusion was inevitable in the heavy smoke caused by the fire of many hundreds of guns at close range. Accident or misunderstanding threw out the attack of part of the British fleet, and the ships at the van and the rear of our line did not succeed in closing with their antagonists. Consequently both the van and the rear of the long French line escaped serious loss. But in the centre of the battle, where Lord Howe personally directed the fight from his flagship "Queen Charlotte," the attack was carried out with brilliant success. The British ships forced their way through the French line, shattering their opponents by an overwhelming fire and forcing them to close action. The "Queen Charlotte" herself attacked the French flagship "Montagne," and after a fierce duel completely silenced her. The other neighbouring British ships similarly engaged in desperate fights with their nearest antagonists.

Sketch (not to scale) is only intended to show generally the initial positions and approach of the British Fleet. |

The ship immediately astern of the "Queen Charlotte" in the British line was the "Brunswick," commanded by Captain John Harvey, in which was serving a detachment of the 29th—Captain Alexander Saunders, Ensign Harcourt Vernon, two sergeants, one drummer, and 76 rank and file. In line with her consorts the "Brunswick" bore down on the enemy. As soon as the British came within range the French guns opened fire, and the "Brunswick" suffered many casualties. But with grim discipline the British ship held her fire. The ship's band, stationed on the quarter-deck and reinforced by the one drummer of the 29th, struck up a lively tune, the then new and popular song of "Hearts of Oak." Under a hail of shot from the French guns, Captain Harvey steered for a gap between two of the French ships. The rearward of the two French ships—"Le Vengeur" — increased her pace to close the gap, but "Brunswick" resolutely held on her course until within point blank range. Then (at 10.10 a.m.) Captain Harvey gave the word, and "Brunwick's" guns opened fire with a succession of shattering broadsides. The two ships were rapidly nearing each other, but neither would give way, and (at 10.15 a.m.) they crashed into each other and became interlocked, "Brunswick's" starboard anchor hooking into "Vengeur's" port fore shrouds and channels. Thus locked, so that their upper bulwarks were only separated by a gap of a few feet, the two ships slowly swung round and drifted to leeward, fighting furiously. The two ships were well matched. Both were classed officially as of seventy-four guns — thirty-six on each broadside and two astern. The "Vengeur" was slightly bigger than "Brunswick," and carried more men — 700 against the 600 of the British ship. On the crowded gun-decks the slaughter was terrible as at each discharge the enemy's round shot came crashing through the wooden sides. But the training and discipline of the British guns' crews enabled them to load and fire their guns faster than their opponents, and as the ship rolled the British sailors alternately elevated and depressed their guns, firing them upwards or downwards point-blank into the enemy's side. A desperate fight raged between the open upper decks of the two ships. Musketry and the fire of light carronade(5) swept the bulwarks, and men were hit in rapid succession. On the poop the detachment of the 29th, their red coats showing proudly through the smoke, loaded and fired with the swift precision of trained soldiers; and their musketry withered each attempt of the crowded enemy to board the British ship. But the losses were severe, and nearly half the detachment were shot down. Captain Saunders and ten of his men were killed, Ensign Harcourt Vernon and twenty of the rank and file were wounded. Even in the midst of that desperate fight there was one humorous incident. Through the drifting smoke a small deputation of seamen came hurrying along the shattered deck to tell Captain Harvey that a shot had carried away the wooden cocked hat which surmounted the ship's figurehead—a carved effigy of His Royal Highness the Duke of Brunswick—and that it ill became His Highness thus to be bare-headed before the enemy. Whereupon the gallant Captain presented them with his own best gold-laced cocked hat, which surmounted the figurehead(6) for the rest of the day. |

Captain Harvey himself had already twice been hit, Eventually he was again struck and his arm shattered by a flying fragment of shot. Faint from loss of blood, but refusing all help, he slowly made his way below for medical assistance, after adjuring all to fight to the last.

Presently through the drifting smoke, another French ship loomed up—the "Achille," closing on the "Brunswick's" disengaged port-side. The port guns of the "Brunswick," hitherto silent, broke out with one shattering broadside which brought the "Achille's" masts crashing down. She drifted away disabled, and presently struck her flag.

For two hours "Brunswick" and "Vengeur" continued their desperate duel. By that time the two fleets had lost all formation, and the ordered battle had dissolved into a medley of ships scattered over a wide expanse of sea. The wind was rising again and the sea was running higher. At 12.45 p.m. a heavy roll of the two ships tore the "Brunswick's" anchor away from the shrouds of the "Vengeur," and the two ships, shattered but still firing at each other, swung apart.

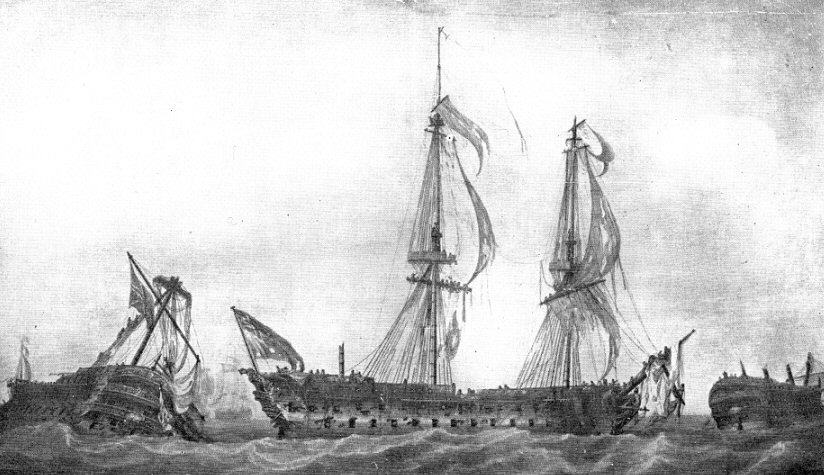

H.M.S. "Brunswick" engaged with the "Vengeur" to starboard and the "Achille" to port

(The detachment of the 29th Regiment can be seen on the "Brunswick's" poop)

Another British ship, the "Ramillies" — also, as it chanced, carrying a detachment of the 29th, and commanded by a brother of Captain Harvey of the "Brunswick" — came up on the further side of the "Vengeur" and poured one deadly broadside into the French ship. The "Vengeur's" fore and main masts fell, and the disabled ship rolled helplessly in the sea, only the stump of her mizzen-mast still standing. At 1.0 p.m. those still standing on the deck of the "Brunswick" cheered and cheered again as they saw the French flag hauled down from the "Vengeur's" remaining yard arm and a Union Jack hoisted in its stead—the stubborn enemy had surrendered.

The "Ramillies" moved on to finish off the crippled "Achille," and the survivors of the "Brunswick" cheered her on her way but it was not possible to take possession of the beaten "Vengeur," for all the "Brunswick's" boats had been shattered by fire. Her sails were riddled by shot, her mizzen mast had fallen, and the situation appeared perilous indeed when shortly afterwards a large part of the French fleet gradually approached. Still the spirit of Captain Harvey and his men was indomitable. All made ready to fight to the bitter end; but the danger passed. The French admiral had no desire for further action, but was only rallying and re-forming his fleet before drawing off to port; and presently the disabled "Brunswick" was rejoined by other British ships.

vening came on. The wind was rising, and at each roll the shattered "Vengeur" was sinking lower in the sea. Three British ships, "Alfred," "Rattler" and "Culloden," came up and sent their boats to rescue her crew; and some 400 of her people(7) were taken off. But some brave men refused rescue, remained on board their ship, and presently rehoisted the French colours. The British ships humanely forebore to fire, for the "Vengeur" was sinking fast. Lower she sank and lower. Then, as the waves splashed over her bulwarks, the little group of Frenchmen broke into shouts of "Vive la Republique" and the fierce chant of the "Marseillaise," in final defiance(8) as their ship went down.

By that time the battle was over. The French fleet was drawing away down wind, many of their ships badly damaged, leaving behind them the sinking "Vengeur" and six other disabled ships, which one by one surrendered.(9) They were taken in tow, and the British fleet, battered but triumphant, made their way slowly back to Spithead.

H.M.S. "Brunswick" with the "Vengeur" and Achille" at the close of Battle

(Note the figurehead of "Brunswick")

From a tactical point of view the victory was not complete, for Lord Howe made no attempt to pursue and annihilate his discomfited opponents; and the French admirals could claim that from a strategical point of view they had achieved their object; for, thanks to the time they had gained, the great convoy of foodships from America reached port in safety. Nevertheless, the news of the battle was greeted with immense enthusiasm in England. The fear of French invasion had been very great, and the definite victory gained, with no British ships lost and six French prizes to show, was a tremendous relief. The moral effect of the battle was greater perhaps than its tangible results. The French revolutionaries, brave though they might be, had been proved no match for our men either in seamanship or in gunnery; and thereafter British squadrons seldom hesitated about attacking the enemy even in greatly superior force. Since the battle had been fought out of sight of land there was no obvious name for it to bear, so it was dubbed "The Glorious First of June," and has so remained.

The total losses of the British fleet were about 1200. Of these the losses in the gallant "Brunswick" alone were 158 — over a quarter of the ship's company—and, as we have seen, the detachment of the 29th on board lost half their number killed or wounded.

The detachments of the 29th in the other ships of the fleet did not suffer severely. The total casualties in "Ramillies" were only seven wounded, one being of the 29th detachment(10); in "Glory" which was more hotly engaged, there were fifty-two casualties altogether, including an ensign and eight soldiers of the 29th, all wounded. The detachment on board the "Alfred" lost two wounded. The "Thunderer," which also carried a detachment of the 29th, was at the rear of the British line, did not become closely engaged, and suffered no loss. Thus the total casualties of the Regiment in the battle(11) were twelve killed or mortally wounded, including one officer, and thirty-two wounded, including two officers. It is not, however, by the "butcher's bill" of casualties that the fame of a battle can be judged; and ever since that date "The Glorious First of June" has been a great tradition in the Regiment. The victory has been commemorated in several different ways. Soon afterwards the design of the regimental button was changed and the button, previously plain and simply bearing the number, was ornamented with a laurel wreath. That wreath was said to commemorate the battle,(12) and was retained until the general change, of uniform after the Crimean War. It is possible also that the regimental device of the Royal Lion, for which the earliest date definitely known is 1797, may have been granted to reward the gallantry then shown. But the practice of embroidering the names of battles on the Regimental Colours had not then been introduced, and no battle-honour for that engagement was shown officially until 1909, when it was decided that Naval battles which possessed no definite name should be commemorated on the colours of regiments which had taken part by the device of a Naval Crown with |

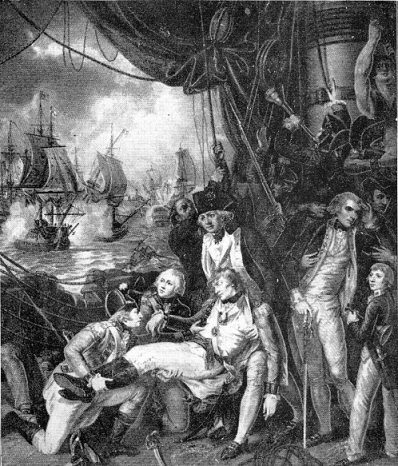

Scene on board one of the ships of the British Fleet |

Better perhaps than any distinction on buttons or on Colours is a living custom which has persisted in the Regiment from that day to this. When the Band finishes its musical programme at any function, "Rule Britannia" is always played before the National Anthem; and the Assembly March of the Regiment has ever since been the tune which the ship's band of the "Brunswick" played as she forged her way onward to close with the "Vengeur" in that memorable fight. To this day anyone who watches a Battalion of the Regiment assembling for parade will hear, as the companies march on to the Battalion parade ground, rising above the tramp of the feet and the shouted orders, the rhythm of the drums and fifes hammering out, even as on the quarter-deck of H.M.S. "Brunswick," the stirring old tune of "Hearts of Oak."

NOTES:

(1) Consequently the first Expeditionary Force sent to aid the Dutch consisted only of three battalions of the Foot Guards. Later three Line battalions, brought up to strength by drafts, followed them to Flanders.

(2) For instance there was then no recognised naval uniform, except for officers—the "ratings" wore any kind of seafaring costume they fancied—nor had the present "military" salute been introduced.

(3) To explain the French admiral's strategy it must be understood that the convoy from America was two days' sailing distance away, approaching from the south-west, and that the wind was steadily from that direction. If he stood and fought, the British, if victorious, would find the convoy sailing right on to the area of battle. If he went south the result would be the same; if he went east, back to port, the convoy would be abandoned to its fate. So he stood west, out to sea, with the British fleet at his heels. His move was successful, and actually the convoy passed on June 1st over the very area which the two fleets had crossed on May 29th.

(4) Five of the British ships—"Alfred," "Brunswick," "Glory," "Ramillies," and "Thunderer" — carried detachments of the 29th, totalling 418 of all ranks, including 12 officers. The detail of these detachments will be found in Everard book, page 152.

(5) Short stumpy guns for use at close range, firing grape-shot which spread like the shot from a modern shot gun—more or less an equivalent of modern machine-guns.

(6) The figurehead of the "Brunswick" can be seen in the last of our three pictures.

(7) Including the Captain and his young son, who were taken off to different ships, and each thought the other dead until joyfully reunited on landing at Portsmouth.

(8) For purposes of propaganda, that gallant episode was exaggerated by the French Revolutionary Government, and became a legend of the whole ship's company refusing to surrender and going down with their ship, cheering to the last. It has remained a famous tradition in France—a tradition so very much alive that, only last year, the writer was astounded to find it staged as a patriotic episode in, of all places in the world, the revue of the "Folies Bergeres” ! The foreground of the scene was the deck of a British ship (presumably the "Brunswick") while the "Vengeur" sank, singing the "Marseillaise," in the background; and to the credit of the stage management it must be recorded that the uniform of the red-coated British officer who removed his hat in salute as the French ship went down was quite recognizable as that of the 29th !

(9) "America," "Impetueux," "Juste," "Achille," "Sans Pareil," and "Northumberland." The last, as the name implies, was an ex-British ship, previously captured by the enemy.

(10) Who unfortunately died of his wounds.

(11) The total strength of the five detachments of the 29th present in the battle was 12 officers and 406 other ranks (Everard book, page 152).

(12) Everard book, page 340.

DETAILS OF OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE 29th FOOT WHO TOOK PART IN THE ACTION ON THE 1st JUNE 1794

Details by ship. Also details of casualties and medals awarded.

BRUNSWICK

Captain Alexander Saunders, Lieutenant Harcourt Vernon and 77 other ranks. .

KILLED IN ACTION

Captain Alexander Saunders, Private William Blood, Private Thomas Grace, Private William Adsley, Private Thomas Lawless, Private David Potts,

Private Henry Wagfield, Private Robert Tod, Private Thomas Brown, Private Samuel Wright, Private Abraham Wright.

DIED OF WOUNDS

Private William Fletcher, Private James May.

GENERAL SERVICE MEDAL (NAVY), 1793-1840.

Private Thomas Robson.

RAMILLIES

Lieutenant James Monsell, Ensign George Dalmer and 75 other ranks.

GLORY

Captain William Jacques, Ensign Patrick Henderson and 98 other ranks.

DIED OF WOUNDS

Private John Ward.

NAVAL MEDAL

Private Stephen Banford—sent to widow, Private James Kilgrove.

THUNDERER

Lieutenant Charles Bulkeley Egerton and 77 other ranks.

NAVAL MEDAL

Lieutenant D. B. Egerton, Private William Robinson.

PEGASUS

Officers: Nil. and 17 other ranks.

ALFRED

Lieutenant Robert Harrison, Lieutenant John Tucker, Ensign L. Augustus Northey and 76 other ranks.

NAVAL MEDAL

Ensign L. A. Northey. Corporal Robert Cook. Private Thomas Smith.

NOTE: The above details accounts for 10 Officers and 420 other ranks.

the appropriate date; and both The Queen's and our own Regiment were granted the device which is now one of our most cherished honours. Apart from being one of the few battle honours for service on ship-board, this device is also remarkable as being almost the only instance of a battle honour given for the services of detachments — for the rule, which in nearly all cases has been strictly enforced, is that headquarters and the greater part of a battalion must be present in order to qualify for a distinction on its Colours.

the appropriate date; and both The Queen's and our own Regiment were granted the device which is now one of our most cherished honours. Apart from being one of the few battle honours for service on ship-board, this device is also remarkable as being almost the only instance of a battle honour given for the services of detachments — for the rule, which in nearly all cases has been strictly enforced, is that headquarters and the greater part of a battalion must be present in order to qualify for a distinction on its Colours.