The Sikh Wars

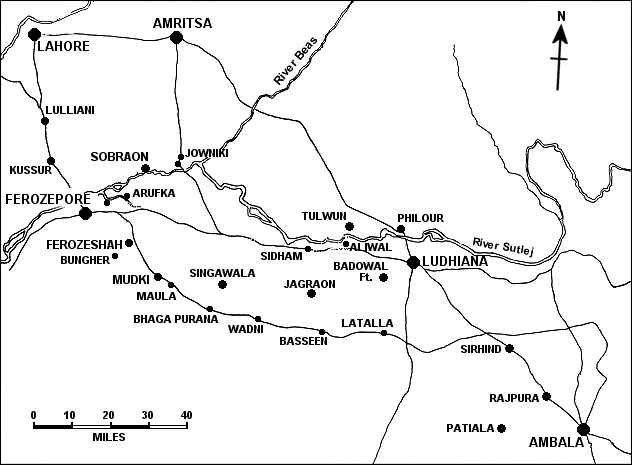

In 1842 the 29th of Foot Regiment travelled to Mauritius and then on to India. The principal independent state in India was that of the Sikhs in the Punjab, which covered an area from Kashmir to the River Sutlej. This part of India was rule by the famous Ranjit Singh, an Indian Maharaja, who established himself as the leading Sikh chieftain after seizing Lahore (1799) and Amritsar (1809). In 1809 he made a treaty with the British Government , by which he agreed not to expand his domain south of the Sutlej River. However, he built up a formidable Sikh army “the Khalsa” with the help of French officers who instructed and transformed the Sikh army into a well trained and disciplined force of about 40,000 men. The Sikhs now rapidly expanded their holding to the north and west of the Punjab region.

Ranjit Singh “the old Lion” had always maintained friendly relations with the British government but after his death in 1839 the Punjab fell into a state of disorder in which a succession of rulers were rapidly overthrown by the army. By 1843 the ruler was a boy, the youngest son of Ranjit Singh, whose mother was proclaimed queen regent. However, actual power, resided with the army, which was itself in the hands of "punches," or military committees. Relations with the British had by now already been strained by the refusal of the Sikhs to allow the passage of British troops through their territory during the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1838-42. Until 1838, the British troops on the Sikh frontier had amounted to only one regiment at Sabathu in the hills and two at Ludhiana with six pieces of artillery, equalling in all about 2,500 men. This total rose to 8,000 during the time of Lord Auckland (1836-42) who increased the number of troops at Ludhiana and created a new military post at Firozpur, which was actually past the Sikh kingdom's dominion south of the Sutlej River. The British had foreseen the impending conflict with the Sikhs and so it was in 1843 the British made preparations for a war when the new governor-general, Lord Ellenborough (1842-44), discussed with the Home government the possibilities of a military occupation of the Punjab. English and Indian infantry reinforcement began arriving at each of the frontier posts of Firozpur and Ludhiana. Cavalry and artillery regiments moved up to Ambala and Kasauli. Works were in the process of erection around the magazine at Firozpur, and the fort at Ludhiana began to he fortified. Plans for the construction of bridges over the rivers Markanda and Ghaggar were prepared, and a new road link to join Meerut and Ambala was started. Exclusive of the newly constructed cantonments of Kasauli and Shimla, Ellenborough had been able to collect a force of 11,639 men and 48 guns at Ambala, Ludhiana and Firozpur. |

Ranjit Singh |

By 1845 the new Governor-General Lord Hardinge took vigorous measures to strengthen the British's military position. He increased the army force to 32,000 and 57 boats were brought from Bombay for making bridges over the Sutlej River. Special training was given to the soldiers. The British troops were now fully equipped and ready for battle.

By October 1845 the 29th of Foot were already stationed at Ambala and preparing for action. The battalion was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel C. C. Taylor, CB, whose Second-in-Command was Major G. Congreve. On his appointment to command, Taylor handed over the 3rd Brigade to Congreve. So prepared were the British that the 29th, with other regiments at Ambala, had received orders to proceed to the frontier on the 10th December.

On the 11th December 1845 the Sikh army crossed the Sutlej River, between Hariki and Kasur and concentrated a great force on the left bank of the river.

|

On December 13, 1845, Governor-General Lord Hardinge issued a proclamation of war and declared all Sikh possessions on the left bank of the Sutlej confiscated and annexed to the British dominions. The British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Hugh (later Viscount) Gough, moved on Moodkee (Mudki ) where he attacked and drove off a Sikh force which was commanded by Lal Singh. Due to a dispatch, which ordered the 29th of Foot to halt, meant that they arrived late for this first skirmish with the Sikhs. During this first bloody battle the Sikhs suffered heavy losses, as did the British with two British Major-Generals killed, Sir Robert Sale and Sir John MaCaskill. Over the past 9 days the men of the 29th had marched some 170 miles over bad roads, deep in dust, in the heat of day and the cold of night. They had also suffered from shortage of water and no bread. It was a tribute to them that on the 21st December at Ferozeshah they went into action (with the exception of the baggage guard) at the same strength as they had commenced their march. |

The Sikhs under Lal Singh were entrenched in a skilfully concealed position. Instead of a frontal assault Sir Hugh Gough moved Taylor’s brigade as part of Gilbert’s division round the Sikh left where the division advanced in echelon of regiments from the right, the 29th leading. Firing as they approached, the men charged a line of guns in front of the Sikh positions. Eventually they breached the Sikhs defences but it was now evening and getting dark, so they decided to withdraw slightly in readiness to resume their attack the following morning.

Although the Sikhs fought bravely once again they were betrayed by their general Tej Singh, who all of a sudden left the field of battle.

As darkness closed, fires broke out in the Sikh camp, mines exploded, and magazines blew up. Pockets of the enemy maintained a harassing fire until midnight and not till then did the British get any sleep. The ground was cold and damp and the soldiers suffered from lack of water.

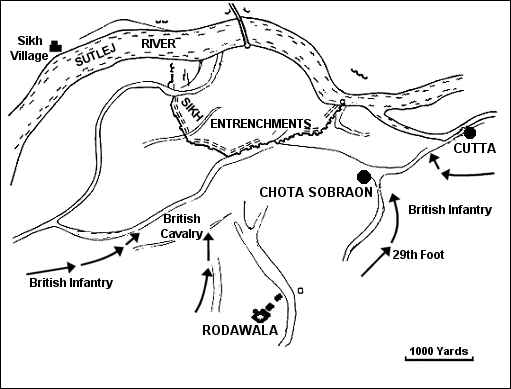

When dawn broke they found that the Sikhs had withdrawn during the early hours leaving over 70 cannon which they had been forced to abandon. The exhausted troops 29th counted the cost of the previous days battle having lost 250 men out of a total of 785. The price of victory, as always against the Sikhs, was heavy. In this battle the Sikhs lost 8,000 men and 73 guns while the English lost 694 men and 1,721 were injured. In January 1846, the Sikhs under Ranjur Singh Majhithia crossed the Sutlej and attacked the frontier station at Ludhiana. On January 28, 1846, Sir Henry Smith defeated the Sikhs at Aliwal, to the west of Ludhiana. The Sikhs commanded by their generals Lal Singh and Tej Singh now retired behind the Sutlej. On 7th February 1846 Sir Hugh Gough received his expected reinforcements. The Sikhs were now in a position, which they had entrenched with their customary thoroughness, at Sobraon. Moving out before dawn on 10th February with Taylor’s brigade leading, Chota Sabraon was occupied and from here at 10.00 hours the attack was launched. The 29th supported by two native battalions dashed towards the ramparts of clay and wood (in some places ten feet high), which the enemy had erected. The attackers could see nothing but the muzzles of the guns behind which the enemy infantry were posted in entrenchments four deep. After two unsuccessful charges, the 29th succeeded in reaching the first Sikh trenches. The enemy suffered terrible carnage and by the end of the battle had lost some 10,000 men and 67 guns. The British losses, too, were heavy suffering 2,383 killed or wounded, out of which the 29th’s casualties numbered 186 out of a total strength of 552. |

Sir Hugh Gough |

|

On the 20th February 1846 the British army occupied Lahore and a treaty was concluded on the 9th March 1846. Thus ended the First Sikh War. |

Shere Singh was now joined by Chattar Singh’s army bringing his strength to 30,000 against Gough’s 13,000. When the British closed Gough was, therefore, fairly cautious. The enemy were in positions at Chillianwallah stretching some six miles from the low hill at Rasul to Mung on the right. The country in front was mostly thick scrub and movement was difficult, but on the Sikh left in front of Rasul the approaches were fairly open. At 0700 hours on 13th January 1849 Gough advanced with the intention of forcing the enemy left flank, which task was given to Gilbert’s division. Mountain’s brigade with the 29th of Foot was on the right and on their left was Pennycuick’s brigade. Shere Singh, perceiving the British intention, seized a small mound near Chillianwallah causing Gough to alter the line of advance to the village. Nevertheless, he did not intend to assault until the next day.

While the troops were piling their arms and unsaddling the horses Lieutenant MacPherson, of the 24th of Foot, climbed a tree and was appalled to see masses of turbans moving through the undergrowth. Bugles were sounded and the British took up their positions for attack. Moving up the guns Gough ordered the advance to commence at 0300 hours. As the advance passed through the thick undergrowth, it was subjected to heavy fire from the Sikh sharpshooters. This caused the orderly line to disintegrate into a series of small groups that, when they debouched into the open, came under the enemy artillery which poured grape into their ranks. The situation on the right was retrieved by the action of General Colin Campbell with the 61st and in the centre by Congreve who, seeing that the 29th were suffering from the fire of a particularly dangerous Sikh gun, charged it himself. Then commenced a struggle of the utmost ferocity. The Sikhs cast aside their matchlocks, and sword in hand fought desperately until overwhelmed. The battle was by no means over. Pennycuick’s brigade had suffered heavily and the 29th were ordered to change front to cover the gap that had occurred. Congreve, noticing that the enemy was attempting to withdraw its guns, turned the 29th about and charged. Sikh cavalry were now seen moving up but checked their pace within 200 yards of the 29th. Every British firelock was brought up to the present and as they fired Sikhs dropped from their saddles and horses rolled over. Another volley completed the confusion and the survivors galloped away. Reforming line the regiment continued to advance; meeting some Sikh infantry who were engaging Pennycuick’s men they charged. Six of the guns that had been supporting the Sikhs limbered up and got away, but the seventh turned round and, taking a shot at the colours, succeeded in clearing away every man around them. The gun was captured, however, and the gunners bayoneted; the gallant 24th who had taken the brunt of this action was saved further loss. In this battle the centre of the Queen’s Colour was shot out and its bearer, Ensign Smith, was twice hit by bullets. This brave officer died at Vazirabad on 29th November. In a letter home just before he died, Smith gave a vivid account of the attack: |

29th at Ferozeshah and Sobraon |

1st Sikh War Campaign Medal |

“An immense line of infantry was standing behind the bushes of their their swords, awaited our attack. Some ten or twelve stood close before our colours; they were fine large fellows dressed in red jackets with green facings; they fired, but missed us, we dashed at them round the bush, one of the men on my right shot one dead, and dashed his bayonet at another, who however seized the dreaded point with his left hand, and cut down his assailant. I came next, the Sikh threw the bayonet away and turned towards me, holding his sword straight up in the air ready to put my head between my heels. I hit in the very nick of time, and making a plunge at him, he looked at me for a moment, and then dropped off my sword, the point of which had penetrated beneath his right shoulder blade.. .. One man threw out his arms, took the point of a bayonet into his body, and held it there with his left hand whilst with his right he severely wounded his antagonist.” This battle was the last occasion on which the colours of any battalion of the regiment were carried in action. This account indicates something of the ferocity of this terrible struggle—one that the British won but over a very gallant enemy. An obelisk was subsequently erected in memory of the British who lost their lives at Chillianwallah. Among the natives the battle goes by the name of ‘Katalgarh’, the House of Slaughter. On the 21st February, the Sikhs retired to Goojerat (Gujrat) where after a two and a half hour bombardment Gough launched his attack. In less than two hours Goojerat fell and British cavalry were in pursuit of a beaten enemy. British losses were comparatively light but those of the Sikhs were enormous. On the 12th March 1849, their army was broken and they had to admit defeat. This decisive victory ended the Second Sikh War. Their leaders were permitted to surrender at discretion and the Punjab, for the possession of which we had not fought, Lord Dalhousie, the governor-general, annexed all the Sikh territory to British India on the 30th March 1849. There were no more quarrels with the Sikhs and the regard of the one race for the other from this moment has been mutual. CLICK HERE TO READ COLONEL GEORGE CONGREVE LETTERS OF THIS TIME |