Captain William Leefe Robinson, V.C. - Taken Prisoner of War

No one had yet appreciated fully the value of the Bristol as an offensive weapon, and Robinson was not experienced in the new fighter tactics being evolved over the Western Front at this time. He was thus totally unprepared for a clash with Germany's most famous and successful flying ace.

Leutnant Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen ("Red Baron"), leading a kette of five twin-gun Albatros D111 fighters from Jagdstaffel II, engaged the six Bristols with an attack "which was similar to a cavalry charge." The Germans scattered the twin seaters and within minutes four had been forced down behind enemy lines. Vizefeldwebel Sebastian Festner brought Robinson down near Mericourt, and both he and Warburton were immediately captured. They were held for a few days in Karlsruhe, and then transferred to the prisoner-of-war camp in Freiberg-in-Breisgau.

The loss of four out of six new Bristol fighters came as a blow to the hard pressed R.F.C., now fighting a desperate and losing battle against a momentarily superior enemy. But the loss of Robinson himself came as a much heavier blow. There were reports that he had been killed, and the news stunned the nation. A letter, written to his beloved Joan, confirming that he was a prisoner, but safe, brought much relief to the many people who, though they did not know the airman personally, had his welfare very much at heart.

For Robinson the next twenty months were far from easy. He was as well known in Germany as he was in England, and this frequently made life unpleasant for him. There is much evidence of maltreatment of prisoners, and Robinson seems to have always been on the receiving end wherever he was sent. His V.C. was only one reason for this. Another was that he was an inveterate "escaper."

Shortly after his arrival in Freiburg he wrote to his parents. Not surprisingly he puts on a brave face and tries to fill his letter with good news to put his parent's minds at ease. Even Robinson's cheery letters however did not always ,pass the camp censors "uncut."

"I have written two sheets to the best girl on God's earth Joan and have reserved this one sheet for you dear old people. I believe I have already written one letter or P.C. to you from this place Freiburg, at any rate if I haven't Joan will tell you all about it, and how I was transferred to this camp here from Karlsruhe with 19 other officers at the beginning of last month

.... (Three lines censored)

We are really very comfortable here and altogether a very lazy crew. I have two other officers in my room both of whom are receiving parcels so we feed awfully well, and start off with a regular English Breakfast of porridge and bacon every morning—and sausages when we have them. I've got things going here a bit by now. We've formed a committee and I've started a library of English books (Tauchnetz edition) we've already got just over 100 books. We are also getting up a sports club, and hope to get a club room out of the German authorities which we'll fit up as comfortably as we can. So you see life is quite pleasant here —although of course one gets awfully sick sometimes when you think that if things had been a little bit different we would still be on the other side of the wire doing something instead of slacking here out of it all as it were!"

While he was reassuring his parents with talk of sausages and sports clubs, Robinson was busy at another activity which could not be mentioned in his letters. He was helping to dig a tunnel. Though he suffered from claustrophobia he and three friends were attempting to dig under the walls. The attempt came to nothing. It was the first of many frustrating failures.

On 21st July 1917, Robinson again wrote to his parents. This time there was sad news to discuss. His sister Grace had died of malaria.

"In a letter I received from dear little Joan yesterday I learnt of the sad news of Grace's death. I can't tell you what a terrible shock it was—we understood one another so well—I might have done so much more for her. I might have been a far more dutiful brother. And what gives me such pain is thinking you dear ones will have to bear this so many miles away from most of your children. How I wish I were with you so that I could try and bring you some comfort in my own poor way. But as I said to Joan, such a loss as this makes me prize more, if possible those who are still left to me—Joan comes first in one way, you two darlings come first in another. I firmly believe that sorrow does not come into our lives, and go without leaving some good behind — this extra bond of love and sympathy may not be the only good this intense sorrow has left.

After Arthur's death I believe the dear girl was never quite happy — but pray God she has perfect happiness now, and for that let us all be glad to sacrifice our own feelings.

There is a Divine purpose in all things. How I love you dear ones at home—Mother darling you still have your baby boy—for I am always that—and he will always love you dearly and do anything in this world for you.

I am wonderfully well here at present and we have a very good time on the whole. We have founded a debating society now, and have arranged for debates to be held every Tuesday evening. We went to the swimming baths as usual yesterday morning and for a glorious walk afterwards. After climbing a hill we had a lovely view of Freiburg and the surrounding country—which is very beautiful about these parts. I must close now darlings—you know you have the deepest sympathy from your loving son."

Fresh plans were being laid by the dedicated group of would be escapers. After the failure of the tunnel, Robinson and Second Lieutenant Baerlin of 16 Squadron attempted to bribe a guard. The man accepted the offer, but again the attempt failed. The authorities heard of the arrangements, and Robinson and Baerlin were arrested and a date was set for a formal court martial.

With almost incredible cheek Robinson promptly attempted to escape again. The door to a courtyard was opened, washing was hung on lines to conceal movements of the would be escapers, and one locked door stood between the prisoners and freedom. At the last minute Robinson's orderly, a one time locksmith, whose task it was to pick the lock, refused to risk being caught aiding his officers to escape, and would not make the short trip across the courtyard to the outer door. The third plan, so simple in concept but so brilliant, had failed. The inner door was shut, and the Germans knew nothing of the attempt.

A fourth plan was formed within twenty-four hours of the third plan being abandoned. A wood shed was used as cover, and access to a staircase which led into an adjoining church was found, again by digging. A group of officers gathered in the church, a window was opened, and one by one the men dropped down into the street below. The streets of Freiburg had become familiar to the prisoners during their day time excursions. They quickly made their way out of town and split up. Robinson, Baerlin and another officer made their way together towards the Swiss frontier. They travelled at night, and eventually arrived at the border. Four miles outside Stohlingen, and four miles from freedom, they were arrested.

After four attempts in as many months, Robinson's reputation as a troublesome charge was growing. In October came the court martial, at which he was sentenced to a month solitary confinement. Baerlin was sentenced to three months. They were sent to the underground fortress of Zorndorf.

From Zorndorf there was no chance of escape. The dark cells were approached by underground tunnels. The only exit was up a long sloping tunnel which emerged in the centre of a mound ringed by wire and searchlights. Robinson said very little about his time as a prisoner when he returned to England, but without doubt this must have been the worst of his experiences. To a man who suffered from claustrophobia solitary confinement underground must have been a living nightmare.

On the 2nd May 1918 Robinson was transferred to a third camp, Clausthal in the Hartz Mountains. Along with two other officers he was bundled into a train. Immediately an escape was planned. One officer was to distract one of the guards while the other two made a jump for it. The plan was risky, but for one of the prisoners at least it worked. Robinson, furthest from the door, did not make it.

Arriving at Clausthal, Robinson met for the first time one of the infamous Niemeyer twins. Heinrich and Karl Niemeyer were Commandants of Clausthal and Holzminden camps respectively, and their harsh treatment of the prisoners in their charge was a well known fact. They had spent some time in America before the war and had learnt a little English and rather more American slang. Their shouting fits at the prisoners, during which they would go red in the face and utter ridiculous threats, would have been funny in any other circumstances. In the prisoner of war camps, where the Commandants had wide ranging powers, the brothers were feared and hated, not just by the prisoners, but by the German guards also.

Heinrich Niemeyer, known to the prisoners as "Milwaukee Bill," took an instant dislike to Robinson, whose reputation had preceded him. At first life was tolerable. Robinson was not denied the normal privileges due to an officer P.O.W., and his pass card survives, evidence that he was allowed a certain amount of freedom. In view of his preoccupation with escaping, the wording of the card is a little ironic.

"By this card I give my word of honour that during the walks outside the camp, I will not escape nor attempt to make an escape, nor will I make any preparations to do so, nor will I attempt to commit any action during this time to the prejudice of the German Empire. I give hereby my word of honour to use this card only myself and not give it to any other prisoner of war."

The Red Cross ensured that life was as comfortable as possible for all prisoners, and letters from home no doubt helped to keep morale high. Robinson's mail included letters from well wishers who still remembered the "Hero of Cuffley."

Dear Captain Robinson,

I have been knitting a woollen scarf, and I want you to have it, as you are the first V.C. airman of this war, in England.

My mother wrote to Captain Sowrey to find out your address. I dare say you remember that about a year ago, mother sent you your photograph to autograph. We have it in our dining-room, framed, with a Union Jack over it. I have got two photographs of you in my bedroom, and in every other room in the house there is one.

I do hope you will get the parcel alright, as I do not want someone, whom I don't know, or of whom I have never heard, to have it, as I have taken a great deal of trouble over the scarf.

With kindest regards, I remain

Yours very sincerely

Annie C Rogers.

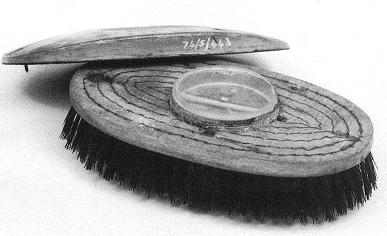

P.O.W.'s home-made compass concealed in a hair brush |

Robinson's time at Clausthal was abruptly brought to an end in July 1918. In his book 'Cage Birds' Squadron leader H. E. Hervey M.C., who knew Robinson well and shared in many of the attempted escapes, remembers his departure. "This month Robinson left the camp. The Commandant had taken an instant dislike to him at their first meeting, probably as a result of Robinson's reputation. Anyway, he seized the first opportunity of getting rid of him, and handed him over to the tender care of his brother at Holzminden. Robinson was a cheerful soul and I regretted his departure, for, since our first encounter at Douai the day after I was shot down, we had moved together from camp to camp. I never saw him again." The last camp to hold William Leefe Robinson was Holzminden. Here, under Karl Niemeyer, there was ceaseless, cruel, and methodical persecution. Robinson got off to a bad start, escaping with another officer, Captain W. S. Stephenson of 73 Squadron. Karl Niemeyer hated escapers, viewing their activities as if they were personal attacks on himself aimed at damaging his position as Commandant and taking away his dignity. When recaptured Robinson was thrown into solitary confinement. Niemeyer raged and fumed at him, shouting in his crazy American-English "You can't fool with me. I know damn all, see!" An unequal feud had begun. |

H. G. Durnford of the R.A.F. was British Adjutant at Holzminden. In his book "The Tunnellers of Holzminden" he describes the treatment meted out to officers who attempted to escape. They were locked in the ground floor cells of "A" Kaserne where the "flies and staleness of the atmosphere were correspondingly oppressive . . . These particular rooms used to be visited two or three times a night by a Feldwebel with an electric torch, which he used to flash on the occupant of each bed in turn, thereby effectively waking everybody up. Here I myself lay . . . and here also lay Leefe Robinson V.C. whose gallant spirit Niemeyer with subtle cruelty had endeavoured for months past to break ... The handling to which Leefe Robinson was subjected was so outrageous that it was communicated to the home authorities in a concealed report (in the hollow of a tennis racket handle) via an exchange party. Robinson had come from Freiburg in Baden where he had made an attempt with several others to escape. 'The English Richthofen' — as Niemeyer with coarse urbanity called him to his face—was at once singled out as the victim of a malevolent scheme of repression. He was placed in the most uncomfortable room in the camp, whereas his rank entitled him the the privilege of a small room; he was caused to answer to a special appel two or three times a day; and he was forbidden under any pretext to enter Kaserne "B". On the occasion of a visit from some inspecting General, and on the pretext of all the rooms having to be cleaned up and ready for inspection by 9 o'clock appel, Robinson's room was entered by a Feldwebel and sentries at 7.45 and Robinson himself was forcibly pulled out of bed and the table next to the bed upset on the floor. Two hours later, Niemeyer was introducing 'the English Richthofen' to the august visitor with a profusion of deaginous compliments, and four hours later Robinson was in the cells for having disobeyed camp orders." |

Escape tunnel found at Holzminden POW Camp |

Hauptmann Karl Niemeyer |

Another British R.A.F. Officer, Lieutenant F. J. Ortweiler, also a POW at Holzminden recorded the following in a statement he gave to the War Office: In another statement to the War Office about the treatment of POW by the Germans, 2nd Lieut. H. G. Durnford (R.F.A.) stated the following about Holzminden Camp and camp Commandant Karl Niemeyer: |