The Regimental Magazine - How it's Produced (1936)

Having been asked to explain how "Firm" is produced, I decided to write this article in the hope of interesting those readers who have never been fortunate enough to visit a printing works. From those who know "how it is done" I crave their indulgence, and ask them not to be too critical. It would, of course, be easier to take you round the works, where you could have expert explanations of the various processes, and perhaps some of you may grant me that pleasure at a later date.

In this article the use of many technical terms have been purposely avoided because of the uselessness in conveying to the uninitiated what I would have them understand. In addition, the article would be much longer and would probably result in boredom. I write it, then, in as simple a way as possible so that you may have some idea how the Magazine is produced.

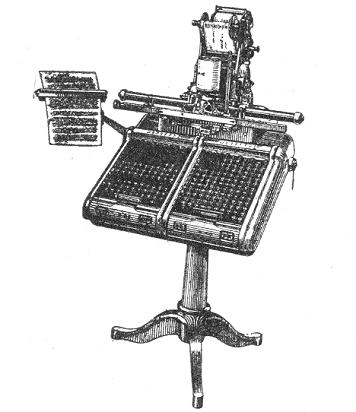

Let us begin by supposing that the Editor has received all the articles, letters, etc., and has handed them into the printers' office. Everything to he included in the Magazine is known from now on as "copy," and after explanations by and discussions with the Editor, "Firm" "copy" is transferred to the foreman of the Composing Room, usually designated in the printing trade as the overseer. In this room the Magazine starts on the first stage of its journey to be set up into type. The overseer goes through the copy, sorting it into proper sequence for setting, and folios each sheet, that is, numbering each sheet from 1 upwards. The type used in the production of "Firm" is set up by the Monotype composing machines. There are a number of different type-setting machines, and the two most in use in this country are the Linotype and Monotype. I will not bother to go into details, but the Linotype is mentioned because, like others of its kind, it works so differently from the Monotype. On the Linotype machine each line of type is cast in one solid piece, whereas on the Monotype each letter is cast separately, hence the two names Linotype (line of type) and Mono (one) type. There are arguments for and against these two ways of setting according to the requirements of the work to he done, and the printers of "Firm" prefer the Monotype. The setting and making of type by Mono is carried out by two operations on two distinct and separate machines—the Keyboard and the Caster, the former of which is worked by compressed air. The Keyboard, as you will see by the illustration, is somewhat like an outsize in typewriters. Some of its characteristics are similar to the typewriter. The actual Keyboard contains seven complete alphabets, Roman (ordinary) type in capitals, small capitals, and smalls (known as lower case), with figures; italics (capitals and lower case), and black capitals and lower case. There are quite a number of size: in the founts of letters, and those most used for book work are known as 6 (the smallest), 8, 10 and 12 point, the last of which produce: six lines of reading matter to one inch. "Firm" is set in 10 point and the name of the type is Gloster. |

Keyboard |

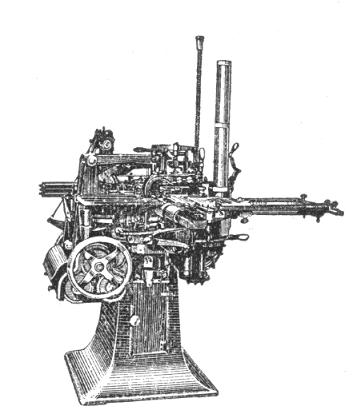

Caster |

Having received the copy, the Keyboard operator, noting the instructions given by the overseer, first makes the measurement on the machine, according to the width of job required; in "Firm" the width is 4 inches (or in typographical terms 24 ems). The English basis for setting is a pica quad (or space), six of which placed side by side make an inch. You will note on the illustration just above the keys a rack runs along the front, and above this there is a circular drum on which are printed numerous figures in sets of two. After making the required adjustments for measurements the operator proceeds to set up the matter. Each time he taps a letter on the Keyboard, a punch at the back of the machine perforates a hole in a paper ribbon which you will notice is unrolled from a spool or reel at the top of the machine. The reel turns slightly each time a key is pressed down. When nearing the end of a line, as in a typewriter, a bell warns the operator of the small space left so that he can ascertain if he has sufficient room on that particular line for the next word. If he has not, he consults the drum which has already been mentioned. According to the number of spaces used between the words in the line, a little pointer has been gradually creeping up the centre of the drum (which also rotates at a certain point), and the operator now depresses the two keys that correspond with the two numbers at which the pointer stands on the drum. By tapping another key, the whole mechanism is returned to zero, and that completes the line as far as the Keyboard is concerned. The perforating in the paper of these two figures which have been registered on the drum sets into motion two justification wedges on the casting machine (which we come to later), and these remarkable pieces of steel automatically evenly distribute the spare space equally between the words in the line. And so the Keyboard operator goes on until he has set sufficient for one perforated roll to be transferred to the Caster. Let me say here that the setting of tabular work entails a great deal more complicated action by the operator, but as it has been decided not to be too technical, I hope the above explanation will give some general idea of the work on the Keyboard. Now we come to the Caster. |

The Keyboard has already decided the order in which the letters shall appear, but it is the Caster that actually casts the faces and bodies of the type, and it is a complicated piece of machinery, the various parts being manipulated with a delicacy that is almost human, and a precision that is undeniably machine like. The perforated paper passes over a small cylinder along the top of which are 33 holes, through which compressed air is forced. When one of the perforations pass over a corresponding hole in the cylinder, levers working a die case place the particular letter required over a water-cooled mould, into which metal is automatically pumped. The die case contains matrices or letter moulds of the alphabet, commas, full stops, etc. The mould makes the body of the letter and the matrices determine the character required and the height of the finished letter; the height of a letter is equal to the width of a shilling. After the letter has been cast, the surplus metal is cut off the bottom and dropped back into the metal pot. The letter is pushed into a carrier and transferred into a channel until the line is completed. Immediately the full line is ready, a small arm draws it away and slides it on to a galley; these operations are repeated until the galley is full. A galley, by the way, is a kind of tray which fits on to the casting machine. As a rule, it accommodates enough lines of type to fill an ordinary newspaper column or approximately three pages of "Firm." When the galley is full, the youngest apprentice (known as the "printer's devil") takes a proof from the type and hands it to the proof-reader and also acts as copy holder.

The proof-reader is a very responsible person; it is he who has to check the printed matter with the "copy," and he checks all errors in spelling, grammar and punctuations. Should there be anything unusual, he must query it for consideration by the Editor when corrected proofs are submitted for final approval.

Now let us turn our attention to the Photographs and Sketches for a while; from these plates or blocks are made for reproduction purposes. For our purpose there are two kinds of blocks. For the reproduction of photographs we require process blocks, and for black and white drawings a line block. A process or half-tone block is the reproduction of an actual photograph through a screen on to a copper plate. If you look through a microscope on one of the reproductions you will find a large number of dots; these are the screen. The number of dots vary according to the kind of block required and the quality of paper on which it is to be printed. For instance, for newspapers or rough surfaces the screen is usually 60 to 85; a smooth surface paper about a 100, and the best reproductions which are printed on art paper (containing a special porcelain surface similar to the paper for the frontispiece for "Firm") are 133 to a 150 screen. A 60 screen block contains 3600 dots to the square inch. The better reproductions need the finer screen and the better paper, and naturally mote expensive is the cost. Line blocks are reproduced on zinc, with only the lines etched on to it; these can be used on any kind of paper with more or less equal results.

Now let us get back to the composing room; the proofs of the Magazine have been returned by the Editor with any corrections, additions, or alterations, together with the list of contents or index. The next process, such as the making of the corrections, has to be carried out by hand; the compositor assembles all the galleys of type together and proceeds to make up the type into page form. Blocks for the illustrations are inserted in their order, top and side margins are calculated (allowing for a trim of the edges of the book when folded and covered), and then the type is locked up in formes containing 16 pages. The pages have to be arranged in order so that when printed and folded they follow in their correct sequence. All this making up is done on what is called a stone. It isn't a stone really, but a steel topped table, absolutely flat; the name "stone" comes down from the old printing days when a stone was used. We now have the formes, consisting of pages of type with margins, locked up. Every page of type is held fast in its place by means of an iron or steel frame, called a chase, and wedges known as quoins. Hence the term locking up. The formes are placed in an electric lift and carried directly down to the machine room, where in due course they are placed seriatim on one of the printing machines. Immediately the forme is put on the machine it is not possible to start printing at once; it has to be made ready for printing. If there are any illustrations, they must be examined and tested for height, for they must conform exactly to the height of the type. Next the forme is planed so as to ensure the surface is all dead level; we would explain that in this instance planing does not consist of shaving of high places as in woodwork, but in passing over the surface of the type a flat piece of wood called a planer to ensure that all the type faces are level. It is then fastened in position on the bed or carriage of the machine. The rollers which supply ink to the face of the type are put into position for action, and the machine man looks to his ink duct or fountain and manipulates it so as to supply the correct thickness of the film of ink, which only long and varied experience has taught him to be requisite for the job in hand. The cylinder on which the impression of the type has to be made has already been packed, and will later on receive two additional sheets, but for the moment these are laid in with a sheet of paper to be used for the work. An impression is taken, after which any remaining low or high parts (light or heavy printing) are made good. One of the two remaining sheets is fastened over the make ready, and another impression is taken for inspection and correction if necessary. Finally the last sheet is fastened on to the cylinder, the position on the sheet is verified by trial, and then a pull is taken and shown to the overseer, and after his O.K. the wheels begin to turn. After this a constant watch is kept so as to retain uniform colour throughout the run ; and to detect any blemishes that may arise on the sheet, through spaces rising, or from a multitude of other causes, unless prevented by the vigilant eye of the minder. The printed sheets are placed on special racks for drying and are shortly ready for the binding department. The above deals with the printing of the inside pages of the Magazine.

The printing of the special cover design is somewhat different to the ordinary inside matter; not only is it reproduced in colours, but also includes gold and silver in its scheme. These are printed from six different line blocks which make up the whole in the following order: Green, silver, gold, yellow (printed over portions of the gold so that uncovered parts of the gold may stand out more brilliantly by comparison), red, and lastly black. As each sheet must go through the machine each time a fresh colour is printed, and as each block must fit into its counter part exactly, one realizes the care and skill required to keep perfect register; especially you have to remember that a damp or dry atmosphere will effect a considerable alteration in paper. Formerly the sheets were fed into the machine by hand in the printing of the cover, but, with the advent of the latest machinery, the sheets are now fed automatically into the machine, being separated and lifted by air and placed against special register gauges which move the sheet into dead register position. These mechanical aids do not necessarily detract from the professional pride which a printer craftsman feels when he sees the colours growing and blending harmoniously together under his watchful eye.

And now for the binding department. Here the sheets containing the 16 pages are folded and each set of 16 is placed in a special position. The art paper reproductions are separated from the interleaving sheets (put there as the sheets are printed) to prevent set-off or smudging. When the folding is completed, a sample Magazine is made up and the illustrations inserted so that the whole can be checked to ascertain that all the sheets follow in correct order, and the illustrations inserted in their proper place. The illustrations, all of which have been printed at the same time on one large sheet of paper, are now separated, and each page stacked in a pile. Now comes one of the most important processes of the work. Piles of each of the 16 sheet sections, together with the illustrated plates, are placed round a long table, starting from left to right in their correct sequence. One of the binding staff then starts collating, taking up section by section round the table, and Magazines as completed are stacked in piles. Next the binder puts each Magazine through the automatic stitcher. This machine inserts the three staples through the back of each Magazine and the inside pages are then ready for the covers. The backs of the Magazines are glued and placed singly into position on the covers. the gage of position being a line that has been printed on the inside of the cover which is firmly drawn over the inside pages ;- as they are covered the (magazines are placed in piles of 10 ready for the cutting machine or guillotine) the edges are trimmed, so many 10's at a time, by a large knife, 32 inches long, driven by electricity, first the front edge, secondly the bottom or tails, and finally the head The books are still kept in tens in order to facilitate checking and packing, which is the final operation before they are sent away for distribution among the units of the Regiment by post, bus or rail. The magazines sent to China, are conveyed direct to the boat, arrangements having been made with the shipping agent.

Note: Article taken from FIRM Magazine, April 1936