On the afternoon of the 2nd September 1916, sixteen airships, twelve from the German Naval Airship Division and four from the Army Division, set out for England on what was to be the biggest air raid of the war. For the first time the two services were combining. The vessels were carrying a total load of 32 tons of bombs. The 'Leader of Airships,' Fregattenkäpitan Peter Strasser, was still determined that his airships would bring England to her knees.

In command of SL11 was Hauptmann Wilhelm Schramm, an experienced airship captain who knew the area he was to bomb better than most of his colleagues. He had been born at Old Charlton, Kent, and lived in England until the age of 15 when on the death of his father, the London representative of the Siemens electrical firm, he returned to Germany and joined the army. He was given his first command in December 1915. Schramm had an experienced crew flying with him that night who had already served with him on several raids in the Zeppelin airship LZ39. They totalled only 16 men, machinists, gunners, 'elevator' man and 'bomb' man, officers and Captain.

SL11 under construction (1916)

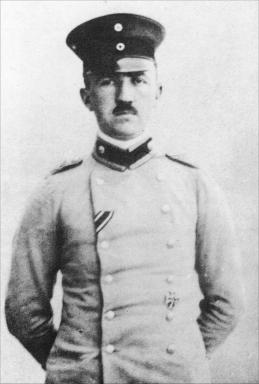

Hauptmann Wilhelm Schramm

Commander of LZ93 and later of SL11

Schramm approached London from the North, passing over Royston and

Hitchin. Consequently he was not the first to arrive over the capital. LZ98 under Hauptmann Ernst Lehmann had that distinction, and by 01.00 hours was heavily engaged by the guns of the Dartford and Tilbury

defences. Dropping his bombs over what he took to be the London docks, Lehmann took his ship up to 13,000 feet. Suddenly an aircraft was spotted approaching the airship. Robinson had seen the Zeppelin caught in the beam of search lights, and had slowly climbed up to meet it. The experienced Lehmann, with a much lighter ship now that his bombs were gone, promptly headed for cloud and continued to ascend. He soon outstripped the night pilot and disappeared. Robinson no doubt cursed his luck. He had already been in the air for two hours, and had only one and a half hours flying time left.

Half an hour later SL11 was wreaking destruction over North London. The Finsbury and Victoria Park searchlights caught her over Alexandra Palace, and the Finsbury gunners filled the air around the ship with explosives. Schramm turned his craft and headed for Walthamstow trying to dodge the fingers of light. Hundreds of people watched, but no matter how close they burst, the ground defence's shells seemed to have no effect. The spectators that night however were treated to a sight that was completely new to their experience. The crowds fell silent. An aircraft, running a gauntlet of shell fire, was fast approaching.

Robinson had given up searching for LZ39, and attracted by the commotion over Ponder's End and Enfield Highway, headed for what he presumed must be another airship. The shell fire grew intense as he neared SL11, and might very well have put an end to his attack before he had got within range. Remembering how LZ39 had so easily outdistanced him as he tried to gain height, Robinson this time headed straight for the airship. The watching crowd below swelled as the news spread that a pilot was within striking distance of the hated

'Zepp'. Suddenly the firing stopped, the searchlights swung frantically, and to cries of despair and frustration from the crowd, the airship found cloud cover and disappeared from sight.

Robinson had his first drum of Brock and Pommeroy ready, and as he flew alongside the airship he riddled its entire length with bullets. He turned his tiny aeroplane around and viewed the Schütte-Lanz. The airship appeared to be completely unaffected by the attack. Robinson fitted his second drum and raked the length of the vessel a second time. Still there was no result. It seemed the massive craft was impregnable. It sailed on almost majestically, as though studiously ignoring the puny aircraft circling below it. To the thousands of spectators it seemed as though a midge was fluttering around a lamp, vainly beating its wings against a glowing bulb. Robinson had one drum of ammunition left, and precious little fuel. Now behind and slightly below the airship, he changed tactics. He dived at the thin end of the craft, heading for the twin rudders above and below the pair of elevators, any one of which was larger than his entire machine. His last drum of ammunition was poured into that one area. Now the guns of the ground defences were silent and all eyes were fixed on the airship, glowing in the searchlights' powerful beams. They had no idea what the pilot was doing. They knew nothing of new incendiary bullets. They did not realise that. as they watched a stream of explosive was pouring into the smallest section of the airship, ripping through its cotton skin. The first indication to them, to the pilot, and probably to the airship's crew themselves, that the longed for victory was at hand, was a dull pink glow from within the rear portion of the ship. Within seconds the tail section was alight, and flames over 100 feet long shot out into the night sky. Almost in an instant the entire hull of the airship seemed to be in flames. Thousands .of cubic feet of hydrogen ignited with a brilliance which lit the sky, turning night into day. The spectators were dazzled. The searchlights were suddenly unnecessary. Observers in Reigate reported seeing the explosion. It was 2.30 in the morning on Sunday 3 September, and 12,500 feet above London a German airship, while in the very act of bombing the capital, had been attacked and completely destroyed.

While London rejoiced, Robinson turned for home. With fuel tanks almost empty he landed at Sutton's Farm at 02.45 hours after a gruelling patrol of three and a half hours. Met by the excited ground crews who milled around the aircraft, Robinson had only to answer a brief affirmative to the question on every man's lips. With a cheer he was borne shoulder high in triumph from his aircraft to the office. Though exhausted and numb with cold Robinson was ordered to write a report immediately.

Lieut. William Leefe Robinson seated in the BE2c 2963

The mechanics hold up the upper wing centre section damaged by his own gun

during the attack on SL11

From: Lieut. Robinson

Sutton's Farm

To: The Officer Commanding

39 H.D. Squadron.

Sir,

I have the honour to make the following report on Night Patrol made by me on the night of the 2nd-3rd instant. I went up at about 11.8 p.m. on the night of the 2nd with instructions to patrol between Sutton's Farm and Joyce Green.

I climbed to 10,000 feet in 53 minutes, I counted what I thought were ten sets of flares—there were a few clouds below me but on the whole it was a beautifully clear night. I saw nothing till 1.10 a.m. when two searchlights picked up a Zeppelin about S.E. of Woolwich. The clouds had collected in this quarter and the searchlights had some difficulty in keeping on the aircraft. By this time I had managed to climb to 12,900 feet, and I made in the direction of the Zeppelin which was being fired on by a few anti-aircraft guns—hoping to cut it off on its way eastward. I very slowly gained on it for about ten minutes—I judged it to be about 800 feet below me and I sacrificed my speed in order to keep the height. It went behind some clouds avoided the searchlights and I lost sight of it. After 15 minutes fruitless search I returned to my patrol. I managed to pick up and distinguish my flares again. At about 1.50 a.m. I noticed a red glow in N.E. London. Taking it to be an outbreak of fire I went in that direction.

At 2.5 a.m. a Zeppelin was picked up by the searchlights over N.N.E. London (as far as I could judge).

Remembering my last failure I sacrificed height (I was still 12,900 feet) for speed and made nose down in the direction of the Zeppelin. I saw shells bursting and night tracer shells flying around it. When I drew closer I noticed that the anti-aircraft aim was too high or too low; also a good many some 800 feet behind—a few tracers went right over. I could hear the bursts when about 3,000 feet from the Zeppelin. I flew about 800 feet below it from bow to stern and distributed one drum along it (alternate New Brock and Pommeroy). It seemed to have no effect; I therefore moved to one side and gave it another drum distributed along its side—without apparent effect. I then got behind it (by this time I was very close-500 feet or less below) and concentrated one drum on one part (underneath rear) I was then at a height of 11,500 feet when attacking Zeppelin.

I hardly finished the drum before I saw the part fired at glow. In a few seconds the whole rear part was blazing. When the third drum was fired there were no searchlights on the Zeppelin and no anti-aircraft was firing.

I quickly got out of the way of the falling blazing Zeppelin and being very excited fired off a few red Very's lights and dropped a parachute flare.

Having very little oil and petrol left I returned to Sutton's Farm, landing at 2.45 a.m.

On landing I found I had shot away the machine gun wire guard, the rear part of the centre section and had pierced the rear main spar several times.

I have the honour to be

Your obedient servant

W. L. Robinson, Lieut.

No. 39 Sqdn. R.F.C.

Then the exhausted airman collapsed on his bed and within seconds was asleep. As he slept the madness of "Zepp Sunday" began.

It is clear that to Robinson and to his fellow pilots, things seemed to get a little out of hand. Robinson was mobbed when he went to view the wreckage on Sunday, so he returned home and changed into civilian clothes. Even so he was recognised and besieged wherever he went. The newspapers made sure that the entire country was familiar with his story, although many of the 'facts' were completely wrong. The pilot could no longer lead a normal life. To make matters worse he was taken off flying duties. He was far too precious to risk. The authorities at last had a Home Defence Hero, a "Zepp Straffer" who had transformed the battle in the air over Britain.

The charred bodies of the SL11 crew

Also the euphoria over the first "Zepp" to be shot down was something of an embarrassment. The airship had not been built in the Zeppelin works, but had come from the Schütte-Lanz factories. To dampen the high spirits with technical explanations was considered undesirable. Morale had surged, and the War Office wanted to keep morale as high as possible. The lack of metal in the airship's charred remains (the main distinction of the Schütte-Lanz airships being that they were made of wood, not aluminium) was explained away in typical wartime propaganda. According to an official despatch issued by Lord French "The large amount of wood employed in the framework is startling and would seem to point to a shortage of aluminium in Germany."

Six pilots were sent up around London and others in Kent and Yorkshire. There were no casualties to pilots, two machines were wrecked.

Operations were interfered with by fog in some districts.

Lieutenant Robinson has done good night work against Zeppelins during previous raids. It is very important that the successful method of attack remains secret, and instructions have therefore been issued that the public are to be told that the attack was made by incendiary bombs from above."

Wreckage of the SL11