Below is a first hand account of a private soldiers experiences during the landing and fighting in Gallipoli in April to June 1915. Private Ben Rubery Ward (11526) was with 'W' Company of the 4th Battalion and wrote this account while he was in hospital recovering enteric and dysentery in June 1915. Sadly Ben died in 1923 (age 32) but his story has survived.

I would like to express my thanks to James Flavell who kindly provided a copy of his great uncles story for publication on this website.

In order to enhance Ben Ward's story, some pictures and maps have been added. Also where Ben used abbreviations an explanation has been added next to it in RED with in brackets.

My

Tales of the Dardanelles (April-June 1915)

by Private Ben Ward (11526) - 'W' Company, 4th Battalion Worcestershire

Regiment

Now we were once again on vessels deck gliding over the foam, our first stop being a small Island that was to serve as our base. It was a lovely little spot, quite a natural harbour, but I did not go ashore; what little land I saw looked lovely, and I had the pleasure of visiting that spot about three months afterwards and found grapes in abundance. We started from there late on the night of April 24th, 1915, heading for the Dardanelles.

Major H. A. Carr

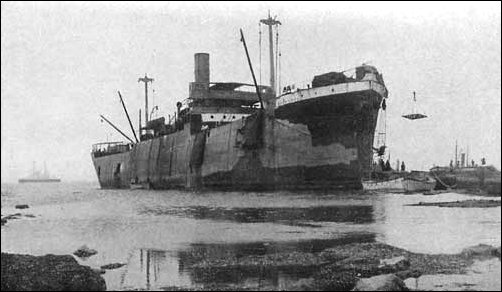

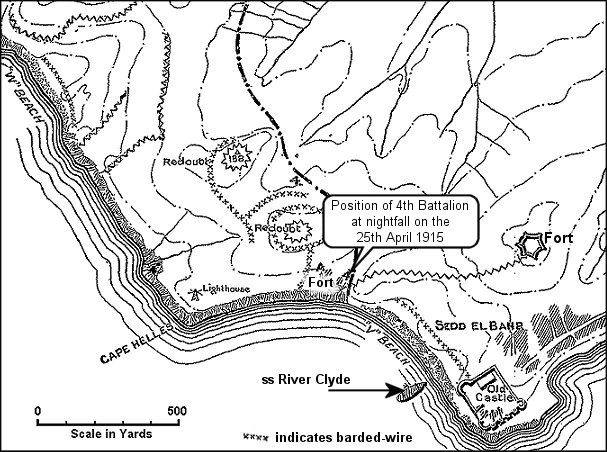

S.S. River Clyde, was purposely run aground on the beach at

Sedd-ul-Bahr to act as a base

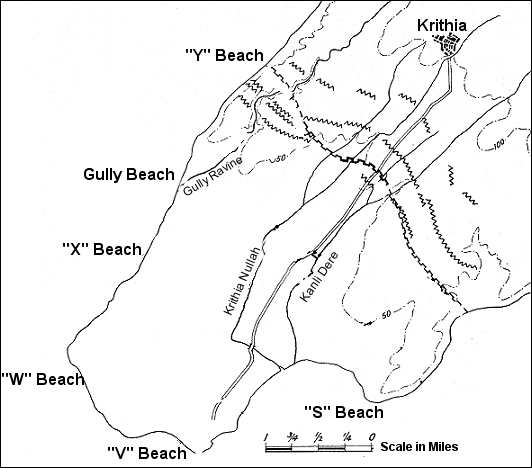

'W' Beach landing area

Landing Beach locations

Now the day was breaking. What a sad sight! The poor fellows could not be taken away during the night, for every rifle was needed, and to get them away only meant death, so they had to remain in the scorching sun. Now we were able to see our position, ft Redoubt on our right and left with barbed wire entanglements, which have to be taken, 'X' Company being detailed to charge the first. Away they went, led by Captain R. (Capt. A. D. H. Ray) running quite twenty yards in front of his men, but he fell being shot through the head, but his death only made the men more furious, and the Redoubt was reached, but the Turks had fled. They did not like the look of cold steel. Here I saw a little Midshipman take a Company of the S.W.B's (South Wales Borderers) into Action. I don't think he could be more than sixteen years of age, but he shouted, "Come on boys, follow me," and away they went, the little fellow with his short cutlass running about fifteen yards in front.

Lieut.-Col. D. E. Caley

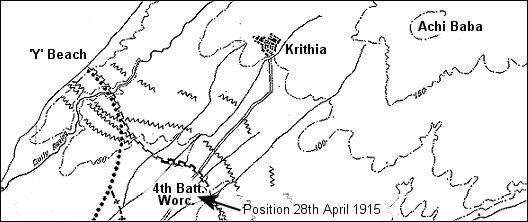

The next day, April 28th, we started our big advance, our Battalion being on the extreme right. We started at six o'clock at night. Then we had to halt as the Peninsular was busy while in this part, and we had no men to take over the new ground. So the General sent over for the French, off the Asiatic side to come to our aid. This, in my opinion, was the real failure of the Dardanelles, because the French were very slow coming to our aid. We were on the slopes of Achi Baba and had the Turks on the run, we had lost quite a number of men, so we had to retire about miles and a half, we met the French coming, but too late to save the position. We were very tired, and expected a night attack by the Turks. The rain was rolling down and we had no great coats, for we had left them behind in the retreat, so we had to grin and endure it, but things turned out better than we expected. The Turks did not attack, they lost a golden opportunity, for we were very short of ammunition, and had only three hundred and sixty men left; but their loss was our gain. The next morning we were sent to hunt through a wood on our right. We had a fine time going through, it brought back memories of the pheasant shooting in Worcestershire, but this time we were out for bigger game, Turkey!!! We did not hunt in vain for we caught a number who would not surrender, shot them, and took eighty prisoners.

Now it had developed into trench war fare, which I had sincerely hoped it never would. It is nothing short of murder, awful to the extreme, and very trying to the nerves. One thing I would like to say about the Turks, they were very good allowing us to fetch in our wounded, that we had left behind on the 28th April. When we got to the Turkish position we found them all placed under trees, with nice cool drinking water by their sides. We expressed our gratitude by shaking hands with the Turkish soldiers, for we thought it very kind. They did not dress any wounds, but I think this was on account of their religion or caste. They always allowed us to fetch our wounded in for weeks afterwards until some one fired on them. Then, of course we had "tit for tat," you could not show a finger above the ground.

We now had to start making our Communication trenches, mule tracks for bringing up the supplies, which was very trying to us all, for we had to hold the trenches and do this in our own spare time. We kept this up till the 1st May, then we started to advance again, it all being explained to us by Lieutenant R. our right flank were to rest on an old tree about two miles in front. The Battalion all started the same time, but it was a long distance to go under shell and rifle fire. Our Company got up to the spot about half past one, but the remainder did not get into position until 4.p.m. They had lost quite a number of men, the ground being awful to advance over, no cover, not even a blade of grass. We entrenched ourselves in under rifle and shellfire, but we could not get any reinforcements up in time to advance again. This was one of the worst trenches I had been in. There was a little stream running through, but each time a fellow went to try and get a bottle of water, he either got killed or wounded. We got relieved from here and went down to "Gulley Beach" to start to make roads for bringing up supplies. The Navy blew the rocks away, it was very hard work lifting those heavy stones, and we were under shell fire most of the time. The Peninsular was not very wide, so we were shelled everywhere we went. We did not stay road making very long, the Fusilier Brigade relieved us, or what was left of us; they would not have made one Regiment, for they got cut up badly landing on 25th April.

On the 8th May, we made another advance towards Krithia Village, advancing about two miles but at a terrible cost. We started about half past eight, from then, until 4.p.m. at night I did not see one Officer of my Regiment. This was the worst predicament I had been in the landing. I did not know what to do, or where to go. I have read Bennet Bernleigh's stories of wars, which he went through. He only saw the English panic stricken once; I think this was on the Indian frontier, and what I saw that day, I quite believe him, for the Troops were scattered all over the place, but they all had the same thing in view - Krishia Village. How grand it is to be British! Nothing daunts them. How I should love the people at home to see them going into action, for no-one can express how grand it looks.

Lieutenant R. (2nd Lieut. A. W. Roberts) asked me to go back with a dispatch to the Colonel. I took it, but didn't realise what a hard job I had taken on hand, for all who have been on Active Service, know how hard and dangerous it is to put a finger above the trench. There was a gully I could have gone down a little under cover, but the dispatch was urgent, so across the open field I went, how I could not tell, bullets and shrapnel, like hail all the way. I met our brave Colonel on the way. Could he be human, or was he a spirit, walking about with a walking stick, and not taking any notice of the bullets or shells? Two bullets had already gone through his walking stick. It was a lovely sight to see so brave a man. I handed him the dispatch, and he read it still standing in the open, and also wrote the answer. He then asked me why I had ventured across the open. I told him, it being the quickest way. He gave me a good talking to, and told me to go back up the gulley. My task was not yet finished. Lieut. R. (2nd Lieut. A. W. Roberts) again asked me to try and get another dispatch through to the Colonel. This time I was not so lucky. When I was about half way across the field, a bullet went through my putties, trousers and sock, but did not even scratch my leg (a miss being as good as a mile!) A shrapnel shell burst a little further on and a lump hit just under my ear, and one small piece went in. This time I had to go more to the right where a number of fellows lay some dead, others badly wounded. I found the brave Colonel up to his knees in water, giving a morphia tablet to a fellow who had been shot through the stomach. He was a good and brave man and the Troops loved him. He told me to tell Lieut. R. (2nd Lieut. A. W. Roberts) to hold on at all costs, again chastening me for coming across the open. He could see when others were in danger, but could not see when he, himself was in danger.

At 4 p.m. that day the remainder of the Battalion got into position after fighting eight hours. We were relieved that night and should have gone back to 'Y' Beach to rest, but the poor fellows were so tired, they dropped down and went to sleep behind the position they had won that day, I daresay you can picture them in your mind, lying there with the beautiful moon shining on the brave fellows. As I lay there, I remember a picture of a soldier I had seen in Miss Sands Soldiers Home in Calcutta, this soldier was standing at bay, with the words written underneath, "God bless you, Tommy Atkins." I feel the Lord did bless them that night, not a single shot was fired. Next day I saw the finest sight I had ever seen. The Australian Brigade, Dublin Fusiliers and N.Z. Regiment advancing. They had the the same ground to cover, that we had covered the day before. The shot and shell fire simply rained in on them, but not once did they falter. I cannot be sure of the date, but I think it was between the 9th and 12th of May we lost one of our 18 Pounder guns, or, rather, the Singalese lost it for us. The Gurkas and our Regiment were ordered to get it back. That was the cleanest task we ever had on the Peninsula, for we caught the Turks in the open and attacked them with the bayonet. They out numbered us, and it took us twenty minutes to get the gun back. We could only take it back inch by inch. I remember the R.F.A. (Royal Field Artillery) made us fifteen dixies of tea, and brought it to us. I never felt prouder in my life, for the R.F.A. told us they were sure of getting their gun back when the Worcestershires and Gurkas had gone for it!

Then we had our rest. Oh, what a rest! Road making, reserve trench making, and even unloading our own provisions off the ships, there being no troops left behind to do it. We were told day after day, week after week, that reinforcements were on the way, but they were a long time coming. That made a lot of extra work for us. Next day we took up a position that the S.W.B. (South Wales Borderers) had taken and held until the 1st of June, making it twenty days in the first line trench without a rest. It was a common sight to see men asleep standing up. We then had a rest until the 4th of June. On that date we were taken back to take part in the Charge.

Our grand old Colonel came back to us after being wounded. We were having a rest in the gully behind the firing line, when the boys started cheering. I thought the war had ended, or something grand had happened. It was not the end of the war, but our brave old Colonel come back to lead us in the Charge, his head still wrapped in bandages. The Turks must have heard us cheering, for when we went over a little later in the day, they were very scared and did not wait for us until we got into their fifth trench. It was a lovely charge. We went over like one man, the brave old Colonel running in front. He was a brave fellow. The biggest coward would have to have followed him. They tried a counter attack that night, but we gave gave them a good surprise and paid them back in full, for we used the maxim guns and explosion bullets that we had captured from them that day.

I shall always remember that day. For General H. (General Sir Ian Hamilton) gave me a Certificate for bravery in the field and mentioned me in Dispatches. I remember they sent for our Colonel the next day to go to Divisional H. Q. but he would not leave us, so they sent a Staff Officer up for him. He was promoted to Brigadier General. So we lost the bravest, and kindest officer a Regiment ever had. He always had a chat with us when he came our way. I have just had a letter from a chum of mine. He says, "The General is alive and well, and may he live for ever!"

We stayed in the Gully until we got reinforced, then we went back into the old trench again to hold it for a few days, we, the H.5. Ess. Reg. I got quite sick of that trench, for there I could see my own chums, dead, That is the bitterness of warfare, looking at them day after day, for we could not remove them, or fetch them in when they were wounded, but only watch them die. I well remember a lad of the Dublin Fusiliers who was lying about fifty yards in front of our trench, we threw him a bottle of water, or rather, mud. The Turks saw the direction the bottle went, and fired, killing the boy. We got back six that night, and four walked in on their own, after being out three days and four nights. What wrecks they looked, and mad with thirst; their lips and mouths bleeding. We left that trench a few days later and I almost jumped for joy, for we went over to the left, to a trench called "Gurka Bluff." It was a bluffy part, dead Turks lying in hundreds, the smell being awful. The Turks put the flag of truce up that day, and asked us to let them bury their dead, but the bodies were too close to our lines, so we could not let them. They paid us back by firing into the bodies when the wind was blowing our way, the smell being terrible. This was another bad trench for water. It was quite two miles away and not at all nice.

That night our grand old Colonel now Brigadier General came and told us that the 11th Division had landed at Sulva Bay, and had made, a good advance. "We were overjoyed at the news, for we had waited long for Mr. Turko to come out into the open, but again we were disappointed. At half past nine that night we had a message to proceed to Sulva Bay, to help the 11th Division who had been cut up most dreadfully. We left that night about 12 , and it was like leaving home, for I had been on that part three months three weeks, and four days, so had got quite used to it. We landed at Sulva Bay early next morning, I again being under shell fire. Our 86th and 87th Brigade at once attacked Chocolate Hill, my Brigade the 88th being kept in reserve, but we had to go up in the afternoon, only to meet with disappointment; for the 86th and 87th were coming back again and how tired and ill they looked, the poor wounded dropping in the lighted bushes, for the shell fire kept lighting the dry bushes. How I prayed for the dear Lord to have mercy on our brave fellows. It was heart breaking to see it all.

We then had to fall back on our a second line of defence and then make a determined stand. We held that position seven days and seven nights. It was a dreadful place, nothing but hills and shrub. We being at a disadvantage on the level, and the Turks on the hills above us. Here again, water was scarce, and we suffered very much from thirst, only being allowed a little over a pint to last us all day and night.

The 11th Division left their dead behind for us to bury, and we also had to collect their guns, stores and equipment from all over the battlefield. The trenches were very poor ones, being made in a hurry, one being made with stone and sand bags piled up together, and one out post being 400 yards in front of the firing line. We had to take fifty men over that night, staying there three days and three nights, and only allowed one pint of water per man to last one day and night. We had to keep very low in the day time, not wanting the Turks to know we were there, for one shell would have finished the lot of us off. One fellow popped his head up to ask for a match and was shot through the head. The Turkish snipers were very good shots.

We then went to Mudros for a rest after holding this trench for eight days and eight nights. We then went back to hold a trench for a while on the left of Chocolate Hill. One funny thing I noticed was we could see not at all, the Turkish trench in front of us, the bushes being so thick, so we could only guess where the Turks were, by their fire. But our boys knew they were there, as we used to creep up at night. We had plenty of water in this trench for we found a little well; but the news soon spread round, and we had men from all Regiments visiting us even the Indians came for a "tora Pawney". At last we were compelled to put a notice up asking each man to take one bottle only, otherwise out little well would be exhausted. There was a lot of illness on this part of the Peninsular. It was awful to see the little chaps just come from England, walking about like living skeletons. It hurt me more than any thing else I had ever seen, they had such nice rosy cheeks when they first arrived, but in a week or so, they looked perfect wrecks. The Medical Officer of my Regiment was so discouraged; he poisoned himself and was found dead in his dug out. Here I saw that grand old fight that Sir I. H. mentioned in his dispatch, the Yeomanry advancing across salt lake, under very heavy rifle fire, I standing behind the first field dressing hospital about thirty yards from the General. I had been in all the advances and charges, but I could scarce believe my eyes to see the boys advancing, shells bursting and making gaps in their ranks, but still they went on until they got to Chocolate Hill. There they got a bit of shelter. I cannot describe this advance properly, it was so grand, yet looked so inhuman to see line after line going over only to be cut down like nine pins, and their places being taken by more brave men.

We worked very hard the next few days making trenches like little forts, for we knew we should not be able to advance again, but have hard work to hold our own. We also had to get the wounded in, it being very difficult to get the poor fellows for we could only go out at night, and some had gone too far. When we saw a body, we had to kneel down and see if he was dead or alive, it was in this trench I contracted enteric and dysentery, (which brought my career in the trenches to an end,) after being eight days and seven nights in a hole at the back of the trench, before I was taken away.

There is a lot I would like to write, but I dare not. Some day I may perhaps, be allowed to. One thing I would like to say, there are a few people in this England of ours, who do not realise the bitter hardships our brave boys are going through, and the self sacrifice that is given all for them, but the dear boys have the satisfaction of knowing, "They die that we might live" they are stopping a crafty foe who is endevouring to seize every thing and all we love. It is the great supreme power, "God doeth all things well." And when a mother loses a son, she should smile a loving and grateful smile. "Greater love hath no man than he who lays down his life for a friend." She should also comfort herself with Mrs. Gurneys poem:! He resteth there who fought with no surrender, wrapped in peace like water cool and bright, Till God shall arouse him again in splendour, to battle with the spirit of the night.

Yes, I would like to write a book and tell all. Perhaps some day I may be allowed, nothing would give me greater pleasure, except my belief in God, to whom I owe all thanks and praise!

Yours faithfully,

BEN WARD.